The Life and Art of Sandro Botticelli

|

|

CHAPTER VII∧ 1475- 1478

Botticelli as a painter of classical myths.

|

第七章∧

1475 - 1478

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

AMONG the Florentine masters of his age Botticelli stands out as the foremost painter of classical myths, the man in whose art the enthusiasm for pagan antiquity, which was the ruling passion of Lorenzo's immediate circle, finds the fullest and most complete expression. This phase of Sandro's art has become of late years almost as popular as his religious paintings. On the one side we know him as the painter of Madonnas, on the other as the master of the Venus and the Pallas, the Primavera and the Graces. Since all the varying moods of the fickle world in which he lived were reflected in his work, it was natural that this, the strongest and most powerful influence of the times, should find a place there.

|

第七章

同時代のフィレンツェの画家のなかで、ボッティチェリは、古典神話の画家として際立っている。ロレンツォの直近の仲間の心をとらえていたギリシャ古典への熱情が、彼の芸術のなかで、最大かつ最も完全な表現を見つけていた。サンドロの芸術のこの段階では、キリスト教の宗教画と同じくらい人気を博すようになっていた。一方では、サンドロ・ボッティチェリが聖母子の画家として、他方ではヴィーナスやパラス・アテネ女神、春(プリマヴェーラ)と 三美神の画家として、我々は知っている。彼が生きた変転する世界のすべての様々な気分が彼の作品に反映されたので、この、時代の最強かつ最も強力な影響が、サンドロの作品の中に居場所を見つけるのは自然なことであった。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

The classical revival which had permeated the literature of the Laurentian age was slowly gaining a hold on the art of the Quatrocento, and affecting both the sculpture and painting of Florence. Painting, indeed, had been so long exclusively dedicated to the service of the Church, that some time elapsed before the prevailing humanism of the day was able to turn its course into new channels. But by degrees the twofold forces of scientific realism and the study of classical models succeeded in transforming Art in all its manifold forms. The passion for building splendid palaces which distinguished not only the Medici but all the great families of Florence, afforded the decorative arts fresh scope for development, and supplied painters with a new field. Vasari tells us that Dello, an artist who flourished in the first half of the century, decorated cassoni with subjects from Greek and Roman history, and myths from Ovid's Metamorphoses. And as a remarkably fine specimen of the artist's skill in this direction, he mentions the furniture of a whole room, which was decorated in this style for Cosimo di Medici's son, Giovanni. The story of Paris, we learn, was among the subjects which Paolo Uccello painted in the Casa Medici. Donatello, we know, reproduced classical motives from antique gems, the legends of Ulysses and Pallas, of Bacchus and Ariadne, of Diomedes and the Palladium in the eight marble medallions with which he adorned the inner court of the palace, and the Pollaiuoli brothers painted their lifesize figures of Hercules upon the walls of the same house.

|

第七章

ロレンツォ時代の文学に浸透していた古典復興は次第に15世紀芸術にその位置を確保し、フィレンツェの彫刻と絵画の両方に影響を与えた。確かに、絵画は長い期間、教会のためだけにあったのだが、当時の人文主義の広まりに応じて、新しい役割を持てるようになりつつあった。しかし、次第に科学的現実主義と古典人文主義の二つの力は、そのすべての多様な形式で芸術を変えてゆくことに成功した。メディチ家だけでなく、フィレンツェのすべての偉大な家系の、華麗な宮殿を建築するための情熱は、装飾芸術に新鮮な発展の舞台を与え、画家たちに新しい活躍の場を提供した。ヴァザーリによれば、世紀の前半に活躍した芸術家デッロは、家具の櫃をギリシャ・ローマの歴史やオウィディウスの「変身物語」からとった主題で装飾した。そして、この方向での芸術家の技能の著しく精緻な手本として、ヴァザーリはこの形式で装飾されたコジモ・デ・メディチの息子、ジョヴァンニのための部屋全体の家具に言及している。ギリシャ神話のパリスの物語は、パオロ・ウッチェロがメディチ邸で描いた主題のなかにある。ドナテルロは、古代の宝石、ユリシーズとパラス、バッカスとアリアドネ、そしてディオメデス、そして宮殿の中庭を飾る八つの大理石製円形浮き彫りのパラスの像を作り出した。ポライウォーロ兄弟は同じ邸宅の壁にヘラクレスの等身大肖像画を描いた。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

The close intimacy that existed between the humanists and artists of Lorenzo's immediate circle produced rich fruit in this direction. Leon Battista Alberti, the brilliant and many-sided man who anticipated Leonardo in the marvellous versatility of his talents as writer, architect, sculptor, painter and musician, and who discoursed to Lorenzo and his companions on summer evenings in the woods of Camaldoli, lays it down as a fundamental principle that the artist should cultivate the society of poets and orators in order to draw inspiration from their eloquence. In his "Treatise on Painting" the same writer gives the artist minute directions for the representation of pagan gods and heroes, Jupiter and Mars, Hercules and Antaeus, Castor and Pollux, as if these themes were the only subjects worthy of the painter's serious attention. Already, when Alberti wrote, it is plain that the antique was rapidly becoming as much the fashion with painters and sculptors as with poets and men of letters. Alberti himself died in 1472, before Lorenzo had reigned in Florence for three years, and when Botticelli was still comparatively unknown. But his treatises on Architecture and Painting were, no doubt, introduced to Sandro's notice by one of the leading humanists of Lorenzo's court.

|

第七章

ロレンツォの直近の仲間の人文主義者と芸術家の間で存在していた親密さは古代ギリシャ文化の復興の方向での豊富な成果を生み出した。レオン・バッティスタ・アルベルティは、著述家、建築家、彫刻家、画家、音楽家としての彼の才能の素晴らしい多様性にレオナルドを予感させる聡明で多彩な人物で、カマルドリの森の夏の夜に、ロレンツォとその仲間たちに講義をしたほどだが、芸術家は詩人と朗読者の交流を促進し、その雄弁から着想を引き出さねばならないことに重点を置いた。アルベルティの「絵画論」で、彼は古代ギリシャの神々や英雄、すなわちゼウスとマルス、ヘラクレスとアンタイオス、カストルとポルックス(ゼウスの子で双子の兄弟)をどのように表現するかを事細かく指示した。まるで、他の主題などは画家のまともな考慮に値しないと言うかのようであった。アルベルティがそのように書いたときすでに、古代志向が急速に詩人や文学家と同じように画家や彫刻家の間で流行になっていた。アルベルティ自身は1472年に死亡した。その3年後にロレンツォがフィレンツェに実質的に君臨することになるが、その頃はボッティチェリはまだあまり知られてはいなかった。しかし、建築と絵画に関する彼の論文は、ロレンツォの宮廷の主要な人文学者の一人によって、サンドロに間違えなく伝えられていた。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

This was Angelo Ambrogini, generally known by the name of Poliziano, from the mountain-town of Montepulciano, where he was born in 1454. The distinguished humanist, who was so intimately connected with the Magnifico and his children, came to learn Greek and Latin at Florence as a friendless orphan, and in his poverty sought the help of this generous patron. At the age of sixteen he translated four books of "the Iliad" into Latin, and won the appellation of Homericus juvenis from the Florentine humanists. At eighteen he wrote his famous musical drama of "Orfeo" during a brief visit which he paid to Mantua with the young Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga in the summer of 1472. But his influence extended far beyond his own productions. When, a few years later, he became Professor of Greek and Latin, the power and eloquence of his genius attracted the most brilliant youths of Florence to his lectures. "His function was to inspire," writes one of the latest historians of the Renaissance, Sir Richard Jebb, "and his gifts were such that his brief span of life sufficed to render him one of the most influential personalities in the history of Italian humanism."

|

第七章

この人文学者はアンジェロ・アンブロジーニである。一般にポリツィアーノの名で知られ、彼が1454年に生まれたモンテプルチャーノの山間の町の出身である。優れた人文学者となったが、もとは、フィレンツェでギリシャ語とラテン語を学ぶために来たのだけれど、貧困の中で、身寄りのない孤児だったので、寛大な庇護者の助けを求めた。それで、ロレンツォ・イル・マニィフィコやその子息と縁ができたのだ。16歳の時、ポリツィアーノは「イーリアス」の四冊をラテン語に翻訳し、そしてフィレンツェの人文主義者から「ホメロスのような若者」の称号を獲得した。1472年の夏に、18歳で彼は、若い枢機卿フランチェスコ・ゴンザーガとマントヴァへの短い訪問中に「オルフェウス」という有名な歌劇を書いた。しかし、彼の影響ははるかに彼自身の作品を超えて拡張した。数年後、彼はギリシャ語とラテン語の教授になり、その天才の能力と雄弁はフィレンツェの最も優秀な若者を集めた。「彼の役割は、霊感を与えること、」最新のルネサンスの歴史家の一人、サー・リチャード・ジェブは、「そして彼がもたらしたものは、彼は短い人生だったけれども、イタリアの人文学の歴史において最も影響を残した存在になったことだった」と記した。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Sandro Botticelli was one of those who fell under the spell of the "Homeric youth," and caught the fire of his impassioned rhetoric. Like his august patron, Angelo Poliziano showed the keenest interest in art and artists. He edited Alberti's works, suggested the subject of The Battle of the Centains and Lapithac to the young Michelangelo for one of his first bas-reliefs, and composed Latin epitaphs for the moments erected by Lorenzo to Giotto in the Duomo of Florence, and to Sandro's master, Fra Filippo Lippi, in the Cathedral of Spoleto. And, just as in later years, the young Raphael sought the help of the humanists of Urbino, of Bembo, and Bibbiena, and Castiglione, in the composition of his great Vatican frescoes, so now Botticelli found inspiration in the poems of the youthful Poliziano.

|

第七章

サンドロ・ボッティチェリは「ホメロスのような若者」に魅せられた者の一人であり、彼の熱情的な話し方に熱狂した。寛大なパトロン、ロレンツォと同じに、アンジェロ・ポリツィアーノは芸術と芸術家に大変鋭い関心を示した。彼はアルベルティの作品を編集し、若いミケランジェロに、彼の最初の大理石高浮彫りの作品の主題に「ラピタイ族とケンタウロスの戦い」を提案し、フィレンツェのドウオモにジョットのため、またにスポレートの大聖堂にサンドロの師匠フラ・フィリッポ・リッピのために、ロレンツォが建立する記念碑のラテン語碑文を作成した。また、後年、若いラファエルが、ヴァチカン大聖堂のフレスコ画の作成にウルビーノ、ベンボ、ビッビエーナ、カスティリオーネの人文主義者の協力を求めたように、当時、ボッティチェリは若いポリツィアーノの詩に霊感による着想を見い出した。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Whether Sandro was able to read the Latin poets for himself remains a doubtful question. Vasari, we know, tells a story of a neighbour whom the painter accused of holding the false opinions of Epicurus, and who in turn charged Sandro with heresy, since without learning (senza aver lettere) and being hardly able to read, he ventured to write a commentary upon Dante. But whether we accept the literal truth of this statement or not, it is clear that Botticelli was familiar with the works of contemporary poets and with Italian renderings of classical authors. The very fact that Vasari describes him as a persona sofistica, seems to imply that he dabbled in philosophy and took part in the arguments and discussions that were so fashionable among the Platonists of the age. The verses of Lorenzo and Poliziano, the prose writings of Alberti, and the dialogues of Lucian were evidently well known to him. And deeply stirred as he was by the realities of the present, the idealism of his nature led him to take delight in romantic themes. His poetic and impressionable temperament was quick to respond to the influences in the air about him, and he felt as few other artists of his day could feel the charm of the old myths which had so powerful a fascination for the finest minds of the age.

|

第七章

サンドロは、自分でラテン語の詩を読むことができたかどうかは疑わしい。ヴァザーリは、エピクロスに関する誤った考えを持っていると言って、サンドロに非難された隣人が、お返しに、学問もなく、読むこともできないくせに、ダンテについて講釈をたれた異端者であるとサンドロを非難したという話を、我々に伝えている。しかし、我々はこれを文言通り真実として受け入れるかどうかはともかく、ボッティチェリは、同時代の詩人の作品と古典のイタリア語翻訳に精通していたことは明らかだ。ヴァザーリが、サンドロを「探究心の人(ペルソーナ・ソフィスティカ)」と評したまさにその事実が、サンドロが哲学に手を出し、同時代のプラトン学派の中で大変盛んだった議論と討論に参加したことを意味するようだ。ロレンツォとポリツィアーノの詩、アルベルティの美文、及びルキアノスの対話を、明らかによく彼は知っていた。現実に深く突き動かされ、生来の理想主義は、彼自身にロマンチックな主題に喜びを感じさせるようになった。詩的で繊細な気質は彼をして、取り巻く空気の影響へすぐに反応させた。そしてサンドロは自分以外の同時代の芸術家がほとんど、サンドロにとっては最高に魅力的な古代の神話に魅力を感じていないと感じた。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Both Antonio Billi and the Anonimo tell us that Sandro painted many figures of nude women that were surpassingly beautiful. After giving us this information the last-named writer adds the following sentence: "At Castello, in the house of Signor Giovanni de' Medici, he painted many pictures which are among his finest works."

|

第七章

アントニオ・ビッリと「アノニモ」は、サンドロが驚くほど多くの美しい女性の裸体画を描いていたことを伝えている。「アノニモ」は、「カステッロにある、ジョヴァンニ・デ・メディチの家で、サンドロは彼の最も素晴らしい作品に属する多くの絵を描いた」と追記している。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

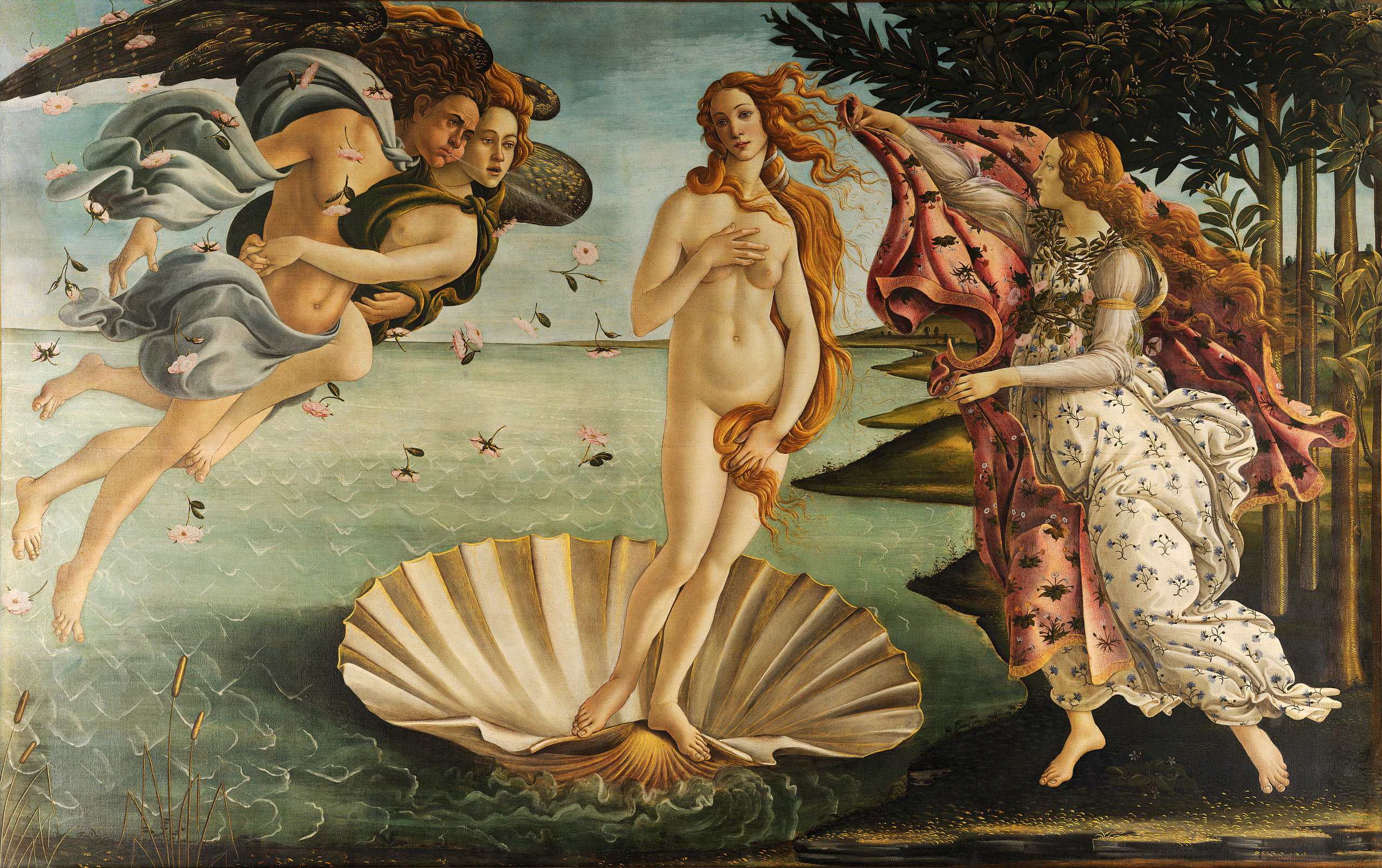

Vasari, who wrote thirty or forty years after the Anonimo compiled his record, confirms this statement, and tells us that in his time two of these pictures by Sandro were still at Castello, a villa belonging to the Duke Cosimo. "One of them," he continues, "is a new-born Venus who is blown to the shore by the Loves and Zephyrus. The other is also a Venus, whom we see crowned with flowers by the Graces to represent the figure of Spring; and both of these the painter has represented with rare grace."

|

第七章

「アノニモ」が記録を編集してから、30年または40年を経て、ヴァザーリはこの上記の言葉を確認し、当時、サンドロによるこれらの絵画作品のうちの二枚は、カステッロのコジモ公の別荘にまだ残っていたと伝えている。「そのうちの一つは、愛とゼフィルスによって海岸に吹き寄せられた生まれたてのヴィーナスである。もう一つもヴィーナスであり、「春」を表現するために三美神によって花を冠されたものである。そしてこれら両作品で画家は気品に満ちた表現をした」とヴァザーリは伝える。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

In this description we recognize the Birth of Venus, now in the Uffizi, and the Allegory of Spring, which is now in the Accademia. There is no mention of these paintings in the various inventories of the Magnifico's collections, and both the Anonimo and Vasari speak of them as belonging to the villa of Castello. This villa, the Anonimo informs us, was the house of Signor Giovanni de' Medici. This was none other than the famous Captain, popularly known as "Giovanni delle bande nere," John of the black bands, the only son of the valiant Madonna of Forli, Caterina Sforza, by her third marriage with the son of Lorenzo de' Medici's handsome cousin Giovanni. This gallant soldier was mortally wounded in a skirmish with the German forces under the Connetable de Bourbon and Frundsberg, then marching on Rome, and died, a few days afterwards, at Mantua in December, 1526. In Vasari's days the villa of Castello was the property of Giovanni's son, Cosimo I, who had by this time risen to supreme power in Florence and had assumed the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany.

|

第七章

この記述は、現在ウフィッツィ美術館にある「ヴィーナスの誕生」と、アカデミア美術館にある「春」(訳者注:現在は両方ともウフィッツィ美術館にある)を示している。ロレンツォ・イル・マニフィコのコレクションのさまざまな台帳には、これらの作品は言及されておらず、「アノニモ」とヴァザーリの両方が、カステッロの別邸に属するものとして伝えている。これは、「アノニモ」によれば、シニョール・ジョヴァンニ・デ・メディチの別邸であった。これは、有名な隊長、ジョヴァンニ・デッレ・バンデ・ネーレ 、別名、黒備えのジョヴァンニである。勇敢なカテリーナ・スフォルツァが、ロレンツォ・デ・メディチのいとこの美男子ジョヴァンニとの三度目の結婚でもうけた唯一の息子としてフォルリに生まれた。この勇敢な戦士は、フランス元帥ブルボン公やフルンツベルクの下でのドイツ軍との戦いで1526年12月にマントヴァにおいて致命的な負傷を負い、その後ローマに行進し、数日後に死亡した。ヴァザーリの時代、カステッロの別邸は、ジョヴァンニの息子のコジモ一世の所有であった。コジモ一世はフィレンツェの最高権力に昇格し、トスカーナ大公の称号を獲得した。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

This double statement naturally leads us to conclude that Sandro's two great mythological pictures were originally painted for Lorenzo di Piero Francesco, the uncle of Giovanni delle bande Nere, and elder brother of that Giovanni who married Caterina Sforza. This youth was the grandson of Cosimo's only brother, Lorenzo, and the head of the younger branch of the house. His father, Pier Francesco, a partner in the Medici bank, and a loyal supporter of Piero il Gottoso and his sons, died in 1474, leaving him a large fortune, and the Magnifico was especially anxious to retain the friendship and support of this wealthy kinsman, who gave him financial assistance on more than one critical occasion. In 1478, when, after the Pazzi conspiracy, Lorenzo was in sore straits for lack of money, he mortgaged his estates at Mugello to his cousin, and betrothed his own daughter Luigia to Giovanni di Pier Francesco. The girl, however, died young, so that this plan for the union of the two branches of the family was frustrated. But the Magnifico employed his elder cousin on several important affairs of state, and sent him to France in 1483 as ambassador to Charles VIII, whose open supporter he afterwards declared himself, when that monarch entered Florence in 1494. But as long as the Magnifico lived, he had no cause to repent of the trust which he reposed in Lorenzo, and the most cordial relations were maintained between the cousins. Lorenzo di Pier Francesco was only two years younger than Giuliano de' Medici, and joined with zest in the jousts and hunting parties with which his cousins amused the gilded youth of Florence. At the same time he shared their literary tastes, wrote songs and Latin verses, and was a generous patron of scholars and artists. Adoration of the Magi which Sandro's pupil, Filippino Lippi painted for the monks of S. Donato in 1496, we may still see the portraits of the different members of this branch of the Medici family. Lorenzo is the dark man in the prime of life, wearing a red mantle. His brother, Giovanni, is the graceful, fair-haired youth in a long green cloak, bearing a gold casket in his hand, while in the gray-headed old King kneeling in the foreground we have the portrait of their father. Pier Francesco. Lorenzo's beautiful villa of Castello, on the heights above Careggi, commanded a splendid view over the valley of the Arno, and was renowned for the extent and loveliness of its gardens. Here Pier Francesco's son entertained the Magnifico and the other members of his family at many a sumptuous banquet, and held splendid festivities in honor of the distinguished guests who visited Florence. Sandro's old patrons, the Vespucci, were among his most intimate friends. Amerigo Vespucci, the great traveller, who was about his own age, took shelter at Lorenzo's villa of Trebbia in Val Mugello during the plague of 1476, and afterwards sent an account of his voyage to his old associate. Amerigo's niece, it is also worthy of note, who was born in this same year, received the name of Piera Francesca. Dr. Brockhaus, to whose researches we are indebted for this information, further remarks that the serpent worn by Simonetta in Piero di Cosimo's famous picture at Chantilly, was the device of Lorenzo di Pier Francesco, who may have employed the artist to paint this portrait of Marco Vespucci's young wife for his own benefit. Angelo Poliziano was also intimately acquainted with Lorenzo, and dedicated the first of his "Sylvae", a poem in praise of Virgil, to this brilliant and accomplished youth, as well as an idyll on the rural charms of the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano. Nothing was therefore more natural than that the Magnifico's rich and accomplished kinsman should wish to decorate his villa with mythological subjects painted by Sandro's hand on themes suggested by the verses of Poliziano.

|

第七章

この二つの記述は、当初、サンドロの二つの偉大な神話の絵画作品が、ジョヴァンニ・デッレ・バン・ネールの叔父であるロレンツォ・デ・ピエル・フランチェスコと、カテティナ・スフォルツァと結婚したジョヴァンニの兄ロレンツォ・イル・ポポラーノのために描かれたと結論づける。この若者は、コジモの唯一の兄ロレンツォの孫であり、一家の若頭であった。彼の父、ピエル・フランチェスコはメディチ銀行の共同経営者で、そしてピエロ・イル・ゴットーゾとその息子たちの忠実な支持者であったが、1474年に亡くなった。彼は大きな財産を残していた。そしてマニフィコは、一度とならず、重大な機会に財政的援助をしてくれたこの富裕な近親者の友情と支持を維持することを特に気にかけていた。1478年、パッツィ家の陰謀の後、ロレンツォが資金の不足のために苦境に陥っていた時、フレンツェの東北のムジェロにある自分の財産を担保にいとこから借金するとともに、娘ルイジアをジョヴァンニ・ディ・ピエル・フランチェスコと婚約させた。しかし、ルイジアは若くして死んだので、二つの分家の同盟はうまくゆかなかった。それでも、マニフィコは、彼の従兄を国のいくつかの重要な役職につけた。1483年にはシャルル八世のもとへ大使としてフランスに派遣されたが、シャルル八世が1494年にフィレンツェに入国した時には、自身をその支援者と公言した。しかし、マニフィコが生きていた限り、ジョヴァンニ・ディ・ピエル・フランチェスコはロレンツォに託した信頼を裏切ることはなく、従兄弟同士の間で最も親しい関係が維持されていた。ロレンツォ・デ・ピエル・フランチェスコはジュリアーノ・デ・メディチよりわずか二歳年下で、従兄のジュリアーノがフィレンツェの陽気な若者たちを楽しませていた騎馬試合と狩猟に参加した。同時に、彼は文学の趣味を共有し、歌とラテン語の詩を書き、学者と芸術家の寛大な支援者であった。サンドロの弟子のフィリッピーノ・リッピが1496年に聖ドナートの修道士のために描いた「東方三博士の礼拝」には、メディチ家のこの分家の様々な人々の肖像を見ることができる。ロレンツォ(・デ・ピエル・フランチェスコ)は、赤いマントルを身に付けた、壮年期の色黒の男性である。彼の弟、ジョヴァンニは優雅で、綺麗な髪の若者で、長い緑色の袖なしマントを着て、金の入れ物を手に持っている。正面で灰色の髪の高齢の博士が跪いているのが、彼らの父親である。カレッジの高台にあるロレンツォの美しいカステッロの別邸は、アルノ渓谷の素晴らしい景色を望み、その庭の広さと美しさで知られていた。ここでピエル・フランチェスコの息子は、マニフィコとその家族の多くを豪華な宴会でもてなし、また、フィレンツェを訪問した著名な賓客を迎えて素晴らしい祝宴を催した。サンドロの古くからの支援者、ヴェスプッチ家の人々は、ロレンツォの最も親密な友人たちであった。偉大な旅行家であるアメリゴ・ヴェスプッチはほぼ同じ年齢であったが、1476年のペストの流行の間にロレンツォのムジェロにあるトッレビアの別邸に避難し、その後、彼の親しい仲間に航海の計画を伝えた。アメリゴの姪は、同じ年に生まれ、ピエラ・フランチェスカと名づけられたことも注目に値する。我々がこうした情報のために頼りにしているブロックハウス博士によれば、シャンティーのコンデ美術館にあるピエロ・ディ・コジモ作の有名な絵画でシモネッタに首飾りとして蛇を巻き付けていることは、マルコ・ヴェスプッチの若い妻の肖像画を描かせるためにピエロ・ディ・コジモを雇ったロレンツォ・デ・ピエル・フランチェスコの考案であった。この作品(訳者注:『シモネッタ・ヴェスプッチの肖像』として有名で、女性が半裸である。シモネッタは1476年に他界しており,この作品が描かれたのは1480年代で、本人を目の前にして描いたものではない。カートライトは第五章で、この作品をサンドロのもののように記している)はロレンツォ自身のために描かせたものである。アンジェロ・ポリツィアーノもロレンツォと近い知り合いだった。ポリツィアーノはこの素晴らしい才能のある若者に、ウェルギリウスを称賛する詩、「森(シルヴァエ)」の第一作とポッジョ・ア・カイアーノのメディチ別邸の田舎の魅力を詠う牧歌を献呈した。それゆえ、マニフィコの裕福な熟達した親戚が、ポリツィアーノの詩で示唆された主題にサンドロの手によって描かれた神話的な画題で別邸を飾ることを望むということは、自然なことであった。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

In 1476 or 1477, the young humanist, who already stood so high in Lorenzo's favour, began to compose an epic poem in honor of Giuliano's tournament. As Luigi Pulci some years before had celebrated the Giostra di Lorenzo in a well-known poem, so Poliziano now abandoned his Homer to sing the arms and loves of the gallant Giuliano. The leading note of the epic is struck in the opening stanzas, in which the poet addresses Lorenzo as the laurel in whose shade Florence can rest in perfect security, and expresses a pious hope that some day he may have the happiness to sing the praise of Lorenzo's name and bear his renown from the Indies to the far ocean, from the Numidian shore to Boutes. But since the task is as yet beyond his strength, he will tune his lyre to another melody, and sing the prowess and the loves of the Magnifico's younger brother. In a series of idyllic scenes, the poet tells the story of Giuliano's loves. First of all, he describes "il bel Giulio," the brave and adventurous youth, whose life is spent in the pleasures of the chase and of study, who is devoted alike to the service of the Muses and Diana, despises women and lovers, and leads a free joyous life in the fields and the woods, while fair nymphs sigh for him in vain. Then he narrates the wiles by which Cupid, determined to avenge this slight, aims his arrow at the heart of the proud youth through the eyes of the beautiful Simonetta, and describes Giuliano's meeting with the lovely nymph in the solitary shades of the forest, and the dream in which she appears to him clad in the armour of Pallas. In a long digression Poliziano takes us to the court of Venus in the island of Cyprus and pictures the gates of the palace, adorned with reliefs of the Venus Anadyomene, the loves of Jupiter, Bacchus, Apollo, and other gods and heroes. There Cupid sings the glories of the house of Medici and returns to prepare Giuliano for the combat in which he is to win fresh laurels. But in his dream, Simonetta is suddenly withdrawn from his sight, in a thick cloud, and the hero, waking from sleep, invokes the help of Pallas and Cupid, and lifts his eyes to the sun, which is the emblem of glory.

|

第七章

1476年または1477年に、すでにロレンツォの好意を集めていた若手人文主義者は、ジュリアーノの騎馬試合を祝して壮大な詩を作り始めた。数年前、ルイジ・プルチが皆に知られた詩でロレンツォの騎馬試合を祝っていたので、ポリツィアーノはホメロスをやめて、勇敢なジュリアーノの戦いと愛を詠うことにした。叙事詩は、ロレンツォを、その木陰でフィレンツェが完璧な安全のもとにいられる月桂樹のようだと呼び、いつの日にかロレンツォの名を称賛する詩を詠い、その名声をインド諸国から遠い海まで拡めるという幸わせを得るような敬虔な希望を表している。しかし、その仕事はまだ当時のポリツィアーノの力を超えているので、彼は竪琴を別の旋律に合わせ、マニフィコの弟ジュリアーノの勇気と愛を歌う。一連の牧歌的な情景では、詩人はジュリアーノの愛の物語を伝える。まず、勇敢で冒険心に富んだ若者、ジュリアーノのことを「イル・ベル(美男子)ジュリオ」と呼ぶ。彼の人生は、狩猟と勉学の楽しみに費やされている。ミューズ(音楽,芸術、学問の女神)とディアナ(狩猟の守護神)への献身に捧げられている。女性と恋人を嫌い、野や森の中で自由に楽しい生活を送っているが、美しい乙女たちは彼を見てはむなしくため息をつく。それからポリツィアーノは策略を語る。キューピッドは、この恋への軽視への仕返しをすることに決め、美しいシモネッタの目を通して、誇りある若者の心に、矢を狙う。彼は、森の孤独な木陰で素敵なニンフとのジュリアーノの逢い引き、そしてシモネッタが鎧を纏ったパラスの姿でジュリアーノの前に現れる夢を語る。長い曲折で、ポリツィアーノは私たちをキプロス島のヴィーナスの宮殿に連れて行き、ウェヌス・アナデュオメネ(海より出づるウェヌス)、ユピテル(ゼウス)、バッカス、アポロ、その他の神々や英雄の浮き彫りで飾られた宮殿の門を描写する。キューピッドはメディチ家の栄光を歌い、新しい月桂冠を勝ちとる戦いのためにジュリアーノに準備させるために戻る。しかし、彼の夢の中で、シモネッタは突然、厚い雲の中を視界から逃げ出し、勇士は眠りから目を覚まし、パラスとキューピッドの助けを借りて、栄光の象徴である太陽に目を上げる。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Here, just as Giuliano is to enter on the Giostra which was to be the theme of his epic, the poet breaks off abruptly at the forty-sixth verse of the second book. In all probability his task was interrupted by the terrible events of the conspiracy of the Pazzi and the murder of Giuliano, after which he never had the heart to resume his song, and the great epic remained unfinished. In this beautiful fragment, however, we have not only the finest of Poliziano's efforts in verse, but the source from which the painters of the Renaissance drew some of their fairest creations. Raphael derived his wonderful fresco of the Triumph of Galatea from this poem, and Botticelli found in it the theme of his loveliest pictures.

|

第七章

ジュリアーノが自分を謳った叙事詩の主題になった騎馬試合に登場するのと同じように、詩人は第2冊目の第46詩で突然作品を中断する。パッツィ家の陰謀でジュリアーノが殺されるという恐ろしい出来事によって、詩人の仕事は中断されたが、その後、詩を継続させる気にならなかった。そして偉大な叙事詩は未完成のままとなった。しかし、この美しい未完の作品については、ポリツィアーノが最高の詩作を行っただけでなく、この作品が元になってルネサンス時代の画家たちが最上級の作品を創造した。ラファエルは、この詩から着想を得て「ガラテアの勝利(1511年)」の彼の素晴らしいフレスコ画を描いた。ボッティチェリも、最も美しい作品の主題を見つけた。

| |

|

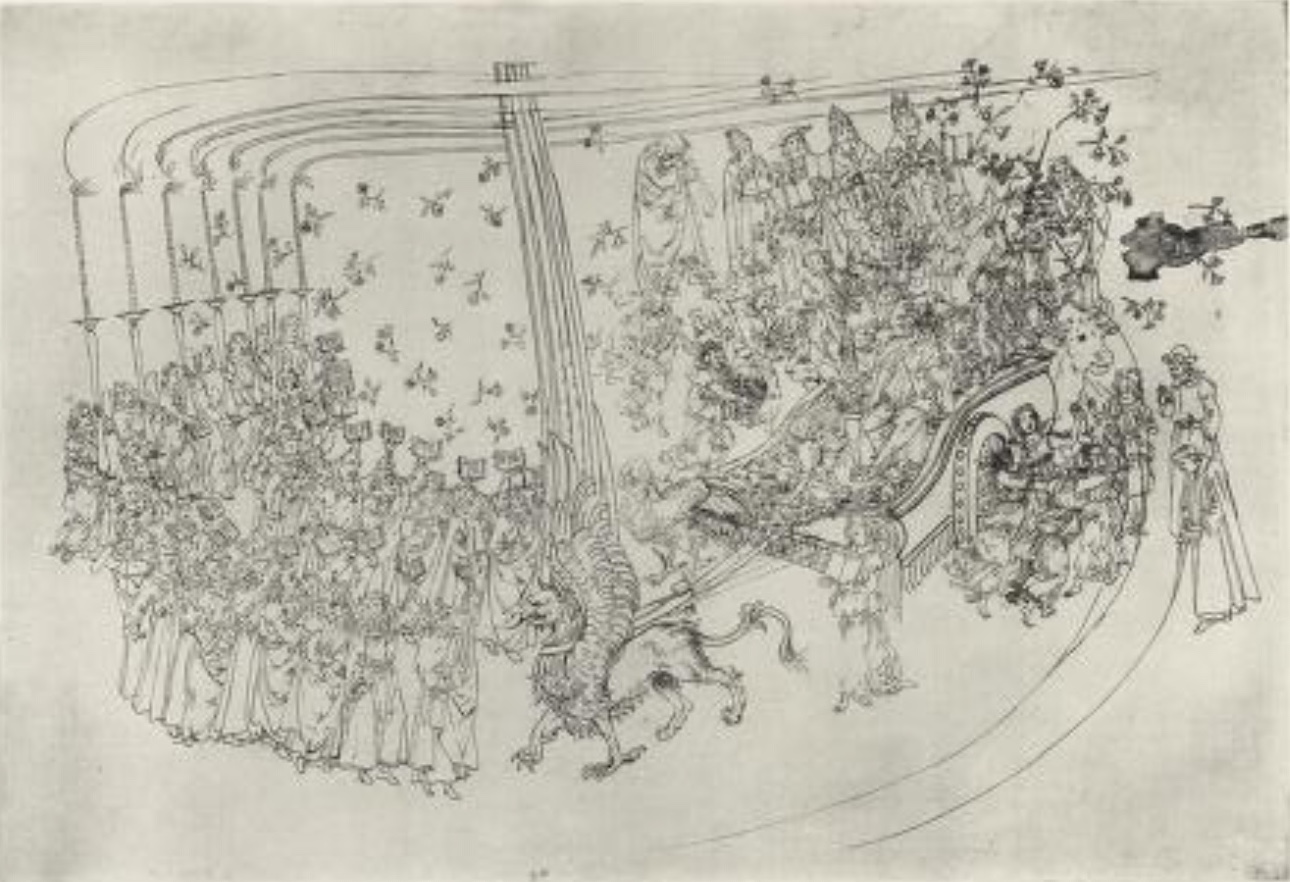

CHAPTER VII

The exact significance of Sandro's famous Allegory of Spring which the Anonimo and Vasari saw at the Medici villa of Castello, and which is now one of the chief ornaments of the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Florence, has been the subject of endless controversy. Some critics maintain that Botticelli owed his conception to the Latin poets, others are equally convinced that he was inspired by contemporary singers. Professor Warburg traces the origin of the composition to Poliziano's Rusticus, "a Latin poem in praise of spring-time, which he wrote at the Medici villa of Fiesole in 1483, and sees in the figure of the god Mercury, a reminiscence of an ode of Horace ("Carm.", I, 30), which had been recently translated by Zanobi Acciauoli. Signor Supino considers Sandro's picture to be an illustration of Lorenzo de' Medici's "Selve d'Amore", while others are equally certain that he found his inspiration in the lines of Lucretius. Dr. Steinmann recognizes the portrait of Simonetta in the form of Venus and that of Giuliano in the figure of Mercury. Several authorities consider the scene represents Giuliano's first meeting with his mistress in the heart of the forest; one German writer, Herr Emil Jacobsen, has framed an ingenious theory, according to which Botticelli here shows us the awakening of Simonetta in the Elysian fields. An Italian critic, Signor Marrai, carrying allegory still further, sees in the different figures emblems of the elemental forces and the powers of Nature renewing their life in the coming of Spring.

|

第七章

「アノニモ」とヴァザーリがカステッロのメディチ別邸で見たサンドロの有名な「春(プリマヴェーラ、春の寓意)」は、現在(訳者注:1904年当時)フィレンツェ美術学校所蔵の主作品の一つであるが、その正確な意義は、際限のない議論の対象になっている。批評家の何人かは、ボッティチェリが古代ローマの詩人に作品の着想の元があると主張し、他の人は同時代の詩人に触発されたと確信している。ワルブルク教授は、「春」の画面構成の起源をポリツィアーノの詩集『ラスティクス (牧歌)』だとしている。「春を称賛するラテン語の詩で、1483年にフィエーゾレのメディチ別邸で書いたもので、メルクリウス神の姿の中に、ザノビ・アッチャイウオーリによって翻訳されたホラチウスの頌歌の回想を見る。シニョール・スピノはサンドロの作品をロレンツォ・デ・メディチが作った詩「愛の森(セルべ・ダモール)」を表していると考えている。他の批評家は同様にルクレティウスの影響があると考えている。シュタインマン博士はシモネッタの肖像をヴィーナスの姿で、ジュリアーノの肖像をメルクリウスの姿で描かれていると考えている。権威のある何人かは、その情景はジュリアーノが森の中でその愛する人との最初の逢瀬を描いていると考えている。ドイツの作家、ヘル・エミール・ヤコブセンは、ボッティチェリはここで、死後の天上の世界でのシモネッタの目覚めを示している、という独創的な理論を構想した。イタリアの批評家シニョール・マライは、「寓意」をさらに引き継いで、異なる姿に春の到来に生命を回復させる要素の力と自然の力の象徴を見ている。

| |

CHAPTER VII

The best interpretation of Sandro's Allegory, we are convinced, is to regard it, in Signor Venturi's words, as a "painted epilogue of Poliziano's 'Giostra'". The particular passage which the artist has chosen to illustrate is the poet's description of the realm of Venus and the coming of Spring. This description, which was one of the most admired portions of Poliziano's epic, he has followed in no servile spirit, adapting it freely to his own uses, and surrounding the creations of his fancy with imagery borrowed from other sources, whether Poliziano and Lorenzo's own verses or familiar passages from classical poets, Lucretius and Ovid. In the composition of his picture, there can be little doubt, Sandro benefited by the help and advice of Poliziano, who, as we have seen, took a lively interest in artistic matters, and was the intimate friend and companion of the Medici brothers and their kinsman, Lorenzo di Piero Francesco. It was, as we know, the habit of these Renaissance lords and ladies to employ the poets and scholars in their service to compose the paintings which artists were desired to execute for the decoration of their houses. Isabella d'Este invariably applied to some wellknown humanist, such as Pietro Bembo or Paride da Ceresara, to supply Giovanni Bellini and Perugino with minute directions for the Fantasie which were to adorn the walls of her studio. In the same way, the members of the Medicean circle may well have sought advice from the brilliant young poet who early learnt to tune his lyre to courtly uses. Poliziano probably discussed all the details of the picture, which Sandro was to paint for the halls of Castello, with Lorenzo di Piero Francesco and his friends, while the Magnifico himself, as the leader of fashion and arbiter of taste in Florence, doubtless took an active part in the discussion.

|

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

The enchanted region where Venus reigns in the isle of the southern seas has been portrayed with exquisite charm by the painter. Here, in a forest glade, under a bower of orange trees laden with golden fruit, and surrounded by a luxuriant growth of myrtle, the Queen of Love holds her court.  Tall and slender in form, but with a certain royal grace in her bearing, arrayed in robes of white and gold and carrying a red mantle on her arm, the goddess advances to welcome the coming of Spring, and invites her guest to enter with a gracious gesture. We see the beauteous Primavera, stepping lightly over the grassy sward, bearing a lapful of roses which she scatters before her as she goes. Her fair hair and graceful throat are wreathed with blue cornflowers and starry daisies; her white robe is garlanded with long-trails of fresh green ivy and briar roses, and patterned over with flowers of every hue. This is truly the nymph of whom Poliziano sings: Tall and slender in form, but with a certain royal grace in her bearing, arrayed in robes of white and gold and carrying a red mantle on her arm, the goddess advances to welcome the coming of Spring, and invites her guest to enter with a gracious gesture. We see the beauteous Primavera, stepping lightly over the grassy sward, bearing a lapful of roses which she scatters before her as she goes. Her fair hair and graceful throat are wreathed with blue cornflowers and starry daisies; her white robe is garlanded with long-trails of fresh green ivy and briar roses, and patterned over with flowers of every hue. This is truly the nymph of whom Poliziano sings:

|

第七章

ヴィーナスが南の海の島で統治する場所は画家が絶妙な魅力で描いている。そこは、森の空き地で、オレンジの木の木陰で、ミルトス(ギンバイカ)の繁茂に囲まれた愛の女王は謁見をしている。背が高く細身の体であるが、その振る舞いには気高い優雅さがある。 白と金の長くてゆるやかな外衣と、腕には赤いマントで盛装し、女神は、春の到来を歓迎するために進み、優雅な仕草で来訪者を招く。私たちは、麗しい春の花の女神が、草地の上に軽く足を踏み出し、衣服に一杯のバラを抱え、進むに従ってそれを前に撒き散らしているのを見る。彼女の美しい髪と優雅な首は青いヤグルマギクと星形のヒナギクに取り巻かれ、彼女の白衣は、長く伸びる新鮮な緑のツタとバラで飾られている。そしてすべての色合いの花の模様がつけられている。これは本当に、ポリツィアーノが歌う、乙女(ニンフ)である。 白と金の長くてゆるやかな外衣と、腕には赤いマントで盛装し、女神は、春の到来を歓迎するために進み、優雅な仕草で来訪者を招く。私たちは、麗しい春の花の女神が、草地の上に軽く足を踏み出し、衣服に一杯のバラを抱え、進むに従ってそれを前に撒き散らしているのを見る。彼女の美しい髪と優雅な首は青いヤグルマギクと星形のヒナギクに取り巻かれ、彼女の白衣は、長く伸びる新鮮な緑のツタとバラで飾られている。そしてすべての色合いの花の模様がつけられている。これは本当に、ポリツィアーノが歌う、乙女(ニンフ)である。

| |

Ma lieta Primavera mai non manca,

|

しかし幸せな春は

| |

|

And this, too, is the fair Simonetta who has conquered Giuliano's heart; the adored mistress whom the poet describes in the first book of the Giostra:

|

そして、これも、ジュリアーノの心を射止めた美しいシモネッタである。詩人が「騎馬試合(ジオストラ)」の第一巻(Iulio e Simonetta)で述べる崇拝された婦人:

| |

Candida è ella, e candida la vesta,

|

彼女は色白、衣も白い

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Whatever may be the exact significance of this fair vision, Botticelli clearly borrowed all this imagery, the rippling hair of gold, and the white robe painted with roses and flowers of varied hue, from Poliziano's description of Simonetta, just as the emerald bough and golden fruit "of the bower of Venus and the green and flowery-meadowed and smiling forest." are used as the setting for his Primavera:

|

第七章

この美しい画面の重要さが正確には何であれ、ボッティチェリは明らかにこのすべてのイメージを使っていた。金色の波打つ房状の髪、バラとそして色合いの異なる花を描かれた白い衣裳、ポリツィアーノのシモネッタの描写から、エメラルド色の枝、ヴィーナスの木陰の黄金色の果物、緑と花の草原と笑顔の森がボッティチェリの「春」の舞台として使われている。

| |

Ride le attorno tutta la foresta.

|

森じゅうを巡る

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

The laughing nymph Flora, who follows closely on the steps of Spring, dropping rosebuds and anemones from her lips, as she flies from the embraces of Zephyr, the blue-robed god of the spring breezes, who tries to seize her in his arms, was no less evidently suggested by Poliziano's lines:

|

第七章

青衣を纏った西風の神ゼフィロスは腕の中にクロリスを捕まえようとするが、クロリスは唇の間からバラの蕾とアネモネをあふれださせ、彼女はその抱擁から逃れようとする。しかし、ゼフィロスがクロリスに触れると、クロリスは笑うニンフのフローラ(花の女神)に変身し、春の足音にぴったり付いていく。この場面はポリツィアーノの書いた詩には、あまり明らかに示されていなかった。:

| |

ove tutto lascivo, drieto a Flora,

|

ゼフィロスはフローラに恋して、その後ろに飛びつく

| |

|

Lorenzo employs the same image in his "Selve d'Amore"

|

ロレンツォは、自作の「愛の森」に同じ情景を書いている。

| |

Vedrai ne regni suoi non piu veduta

|

もはやそこは女神の国とは知らず

| |

|

Both poets probably borrowed the image from the following passage of the Latin poet Lucretius:

|

どちらの詩人もおそらくラテン語の詩人ルクレティウスの次の一節からイメージを借りてきた。

| |

|

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

The group of three Graces who, clad in draperies of transparent gauze, dance on the dewy lawn, with hands linked together, was plainly suggested by Leon Battista Alberti, who in his "Treatise on Painting," mentions this subject immediately after his well-known description of the Calumny of Apelles, as having been often painted by the ancients and eminently adapted for treatment by modern artists.

|

第七章

透明な薄衣で覆われ、一緒に手を結んで、露を帯びた草地で踊っている三美神は、レオン・バッティスタ・アルベルティが、その「絵画論」において、この主題はサンドロの「誹謗(1494-1495年作)」のよく知られた描写の後すぐに言及したが、古代人によって何度も描かれ、現代(当時)の芸術家によって大いに翻案されてきているものだ。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

"What shall we say," he writes, "of these three youthful sisters, whom Hesiod names Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia, and whom the ancients painted with laughing faces, holding each other's hands and adorned with loose and transparent robes? Solutis Gratiae zonis (Horace, Carm.," I, 30).  They are supposed to be emblems of Liberality, because one sister gives, the second receives and the third gives back the gift, which conditions must be satisfied in all perfect liberality." Before them goes the god Mercury, whom Horace names in the Ode to which we have already referred, as the herald of Venus and of the Graces ; a stalwart youth, wearing a winged helmet on his thick black locks and red drapery round his strong limbs, who scatters the mists in the tree-tops, with the caduceus in his uplifted hand, all unconscious of the golden shaft which Cupid is aiming at his heart. The presence of the winged boy who, hovering in the air above the head of Venus, draws his bow to let off his shaft, recalls Poliziano's lines when, on the first meeting of "il bel Giulio" with Simonetta, Cupid secretly aims an arrow at the hero's heart: They are supposed to be emblems of Liberality, because one sister gives, the second receives and the third gives back the gift, which conditions must be satisfied in all perfect liberality." Before them goes the god Mercury, whom Horace names in the Ode to which we have already referred, as the herald of Venus and of the Graces ; a stalwart youth, wearing a winged helmet on his thick black locks and red drapery round his strong limbs, who scatters the mists in the tree-tops, with the caduceus in his uplifted hand, all unconscious of the golden shaft which Cupid is aiming at his heart. The presence of the winged boy who, hovering in the air above the head of Venus, draws his bow to let off his shaft, recalls Poliziano's lines when, on the first meeting of "il bel Giulio" with Simonetta, Cupid secretly aims an arrow at the hero's heart:

|

第七章

アルベルティは、「この三人の若い姉妹について我々は何を言うべきか? ヘーシオドスはこの三女神をアグライア(輝き),エウフロシュネ(喜び),タレイア(花の盛り)と(訳者注:現在一般には、左の「愛欲」、中央の「純潔」、右の「愛」とされている)名付けた。古代人は笑顔にこの三美神を描いた。 三美神は互いに手を繋いで、ゆったりした透明の薄衣を纏っていた。帯を解いた三美神(Solutis Gratiae zonis)である。三美神は贈り物の象徴であると考えられているが、それは、一人が与え、二人目が受け、そして三人目に渡し、そして贈り物を返すからである。そしてその条件は完全な気前良さで満足させられなければならないのだ」と言った。三美神の先を行くのがメルクリウス(ヘルメス)である。先に参照したホラチウスがその「頌歌」において、ヴィーナスと三美神の使者である。ぶ厚い黒髪と赤い上衣を強靭な腕に纏い、頭上に翼のついた兜を着けている逞しい若者は、腕を上げて杖で木の上の霧を払っている。キューピッドが金色の矢でメルクリウスの心を狙っている(訳者注:現在ではこの矢は三美神の「純潔」に向けられているとされている)のを全く意識していない。ヴィーナスの頭上の空中に浮揚しながら、弓を引いて矢を放とうとしている翼のある少年の存在は、シモネッタと「イル・ベル(美男子)ジュリオ」との最初の逢瀬を詠ったポリツィアーノの、キューピッドは密かに矢を青年の心に向けるという一節を思い起こさせる。 三美神は互いに手を繋いで、ゆったりした透明の薄衣を纏っていた。帯を解いた三美神(Solutis Gratiae zonis)である。三美神は贈り物の象徴であると考えられているが、それは、一人が与え、二人目が受け、そして三人目に渡し、そして贈り物を返すからである。そしてその条件は完全な気前良さで満足させられなければならないのだ」と言った。三美神の先を行くのがメルクリウス(ヘルメス)である。先に参照したホラチウスがその「頌歌」において、ヴィーナスと三美神の使者である。ぶ厚い黒髪と赤い上衣を強靭な腕に纏い、頭上に翼のついた兜を着けている逞しい若者は、腕を上げて杖で木の上の霧を払っている。キューピッドが金色の矢でメルクリウスの心を狙っている(訳者注:現在ではこの矢は三美神の「純潔」に向けられているとされている)のを全く意識していない。ヴィーナスの頭上の空中に浮揚しながら、弓を引いて矢を放とうとしている翼のある少年の存在は、シモネッタと「イル・ベル(美男子)ジュリオ」との最初の逢瀬を詠ったポリツィアーノの、キューピッドは密かに矢を青年の心に向けるという一節を思い起こさせる。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

The introduction of this motive, as well as the resemblance of Botticelli's Mercury to the portraits of Giuliano dei Medici, afford fresh proofs that in Sandro's picture we have an illustration of Poliziano's "Giostra." As Signor Venturi remarks, this hypothesis is further supported by an old fifteenth-century engraving, which belongs to a "Rappresentazione " entitled L'innamoramente di Galvano da Milano.

|

第七章

こうした動きを導入したことは、ボッティチェリのメルクリウスがジュリアーノ・デ・メディチの肖像に似ているこのと合わせて、サンドロの作品にはポリツィアーノの「騎馬試合(ジオストラ)」の影響があるという新たな証拠となる。アドルフォ・ヴェンチューリが指摘しているように、この仮説は、15世紀の彫刻でさらに支持されている。この彫刻は、「ミラノのガルヴァー恋に落ちる」というタイトルの「表現」と言う作品である。

| |

|

Here the mistress of Galvano appears as the nymph of Spring with her hands full of flowers, while Cupid hovering above her head is in the act of aiming a dart at her lover's heart.

|

この彫刻では、ガルヴァーノの女神は、手にいっぱいの花を持つ春のニンフとして現れ、彼女の頭の上に浮かんでいるキューピッドは、彼女の恋人の心へ矢を向けている。

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

All the leading features of Botticelli's early works are present in this picture. The tall, slender forms and light, clinging draperies of the dancing maidens recall Fra Filippo's angels. The rich gold embroideries which adorn the white robe of Venus, and the pearls in her fair tresses, display the love of ornament which he had learnt in the workshop of the goldsmith-painters. The influence of the Pollaiuoli is still marked in the careful drawing of the nude in the limbs and attitude of Mercury, as well as in the exaggerated curve of the hip which is common to all Sandro's early figures, and is especially noticeable in the Fortezza and the Pallas. At the same time, there is a distinct advance in freedom of style and individuality of character. In the features of the Graces, in the rhythmical movement of their dance, in their wavy locks and wistful eyes, we already recognize Botticelli's favourite types, the forms and expression which are especially associated with his art, while the smile on the face of Spring has the subtle charm that haunts his friend Leonardo's creations. The sense of air and motion that pervades the picture, the swift action of the god Zephyr, the fluttering garments of Spring, are all highly characteristic.  Both in these details and in the varied treatment of the locks of Flora and the Graces we have another proof of his familiarity with Alberti's treatise. After discoursing of the manner in which the passions of the soul are expressed in the movements of the body, Leon Battista proceeds to treat of the motions of inanimate objects. "And since the delineation of movement of hair and locks, of stems of trees and branches, and of drapery in pictures adds greatly to their charm, I should certainly wish that hair should be represented in the following different ways: Sometimes it twists in a circle, forming a knot, at other times it flows on the air, imitating flames; now it curls downwards under other locks, now it is lifted upwards in one direction or another. In the same way, the branches grow upwards and fall back, partly towards the stem, and are partly twisted in the shape of coils of rope. And the same thing may be seen in draperies; as, from the trunk of one tree, many branches are born, so from one fold many other folds are born, and in these folds of drapery all these different movements are seen, so that there is no fold of drapery in which almost all these movements are not to be found. But let these movements, as I always repeat, be gentle and moderate, and set forth the grace rather than the difficulties of art." Sandro had evidently studied Alberti's book attentively and profited largely by his advice, in this and in his later pictures. But what strikes us most of all in his Primavera is that newborn joy in the gladness of spring and the beauty of Nature, which speaks in each delicate bud and tender leaf, and which makes this picture so perfect an image of the delicious May-time which Lorenzo and his companions were never tired of praising in their songs. The old classical myth appears blended with the new spirit and is transfigured by the poet's fancy into a faery dream of the young Renaissance: Both in these details and in the varied treatment of the locks of Flora and the Graces we have another proof of his familiarity with Alberti's treatise. After discoursing of the manner in which the passions of the soul are expressed in the movements of the body, Leon Battista proceeds to treat of the motions of inanimate objects. "And since the delineation of movement of hair and locks, of stems of trees and branches, and of drapery in pictures adds greatly to their charm, I should certainly wish that hair should be represented in the following different ways: Sometimes it twists in a circle, forming a knot, at other times it flows on the air, imitating flames; now it curls downwards under other locks, now it is lifted upwards in one direction or another. In the same way, the branches grow upwards and fall back, partly towards the stem, and are partly twisted in the shape of coils of rope. And the same thing may be seen in draperies; as, from the trunk of one tree, many branches are born, so from one fold many other folds are born, and in these folds of drapery all these different movements are seen, so that there is no fold of drapery in which almost all these movements are not to be found. But let these movements, as I always repeat, be gentle and moderate, and set forth the grace rather than the difficulties of art." Sandro had evidently studied Alberti's book attentively and profited largely by his advice, in this and in his later pictures. But what strikes us most of all in his Primavera is that newborn joy in the gladness of spring and the beauty of Nature, which speaks in each delicate bud and tender leaf, and which makes this picture so perfect an image of the delicious May-time which Lorenzo and his companions were never tired of praising in their songs. The old classical myth appears blended with the new spirit and is transfigured by the poet's fancy into a faery dream of the young Renaissance:

|

第七章

ボッティチェリの初期の作品の主な特徴はすべてこの作品にある。踊っている乙女たちが背の高いこと、細身の姿と軽くてまといつく薄衣は、フラ・フィリッポの描いた天使を思い出させる。ヴィーナスの白い衣を飾る豊かな金の刺繍と、美しい房になった髪の真珠は金細工匠の工房で学んだ装飾への傾倒を表す。ポライウォーロの影響は、サンドロのすべての初期の人物像に共通している股関節の誇張された曲線と同様に、メルクリウスの手足と姿勢の裸体部分の注意深い描写にはまだ顕著である。この作品「春」以外にも、「剛毅」と「パラスとケンタウロス」には特にはっきり見られる。同時に、様式の自由と性格づけの独自性には明確な進歩がある。三美神の特徴では、踊りの律動的な動き、波打つ房状の髪や思いに沈む眼差しに、ボッティチェリの好みを見つけることができる。すなわち、彼の芸術に特に関連した形態や表現である。「春」の顔の笑みはサンドロの友人レオナルドの作品によく現れるいわく言いがたい魅力がある。画面全体に拡がる空気と動きの感覚、西風の神ゼフィロスの素早い動き、春の風に揺れる衣服はすべて非常に特徴的である。これらの細部とフローラと三美神の房状の髪の様々な扱いの両方で、我々はアルベルティの論考が当を得ていることの別の証しを得ることになる。魂の情熱が身体の動きに表現される様子を論述した後、レオン・バティスタ・アルベルティは、さらに身体そのもの以外のものの動きに言及する。「そして、作品において髪の毛や髪の房、木の幹や枝や、薄衣の動きの線描がそれらの魅力に大きく寄与しているので、髪を次の異なったやり方で表現して欲しい: 髪の毛は、時には、円の形でひねり、結び目を形成し、他の時には風に乗って流れ、炎のようになる。そうして今度は、他の髪の房の下で下方に曲がり、次には一方向あるいは他の方向に持ち上げられる。同じように、枝は上向きに成長し、一部は幹に向かって垂れてくる。枝は、部分的に縄のとぐろ巻きの形に捻られる。女神が纏う薄衣でも同じことが見られるかもしれない。一本の木の幹から、多くの枝が生まれているように、一つの襞から他の多くの襞が生まれ、薄衣のこれらの襞から全ての多くの動きが見える。これらの異なる動きはすべて見られる。何の動きも見つからない襞はない。しかし、私がいつも繰り返して示すように、これらの動きは、穏やかで節度があるべきであって、芸術の難点ではなく優雅さを明らかにさせよう」サンドロはアルベルティの論考をどうやら注意深く研究し、この作品だけでなく後の作品においても、大変役に立てた。しかし、彼の「春」で最も魅力的なことは、春のうれしさで新しく生まれた喜びと、繊細なつぼみと柔らかい葉のひとつひとつで表現される自然の美しさであり、そのことが、この作品をとても気持ちのよい「五月のひととき」のそれは完璧な表現にしたので、ロレンツォとその仲間たちは、この作品への称賛に詩で応えることに飽きなかった。古い古代神話は新しい精神と融合されて現れ、詩人の想像力によって若いルネッサンスの耽美な夢に変貌させられるのだ: 髪の毛は、時には、円の形でひねり、結び目を形成し、他の時には風に乗って流れ、炎のようになる。そうして今度は、他の髪の房の下で下方に曲がり、次には一方向あるいは他の方向に持ち上げられる。同じように、枝は上向きに成長し、一部は幹に向かって垂れてくる。枝は、部分的に縄のとぐろ巻きの形に捻られる。女神が纏う薄衣でも同じことが見られるかもしれない。一本の木の幹から、多くの枝が生まれているように、一つの襞から他の多くの襞が生まれ、薄衣のこれらの襞から全ての多くの動きが見える。これらの異なる動きはすべて見られる。何の動きも見つからない襞はない。しかし、私がいつも繰り返して示すように、これらの動きは、穏やかで節度があるべきであって、芸術の難点ではなく優雅さを明らかにさせよう」サンドロはアルベルティの論考をどうやら注意深く研究し、この作品だけでなく後の作品においても、大変役に立てた。しかし、彼の「春」で最も魅力的なことは、春のうれしさで新しく生まれた喜びと、繊細なつぼみと柔らかい葉のひとつひとつで表現される自然の美しさであり、そのことが、この作品をとても気持ちのよい「五月のひととき」のそれは完璧な表現にしたので、ロレンツォとその仲間たちは、この作品への称賛に詩で応えることに飽きなかった。古い古代神話は新しい精神と融合されて現れ、詩人の想像力によって若いルネッサンスの耽美な夢に変貌させられるのだ:

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Ben venga maggio

|

第七章

五月よ、ようこそ

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

Even today, when time and neglect have darkened the soft blue of the sky and the glossy verdure of myrtle and orange leaves, and dimmed the bright hues of flowers and fruits, Sandro's Primavera remains one of the most radiant visions that has ever dawned on the soul of a poet-painter. How much more must the loveliness of the young Florentine master's painting have called forth the admiration of the humanists who met that joyous springf-time in the fair gardens of Castello! But a tragic doom hung over these dreams of youth and love:

|

第七章

時間の経過と怠慢が、画面の汚れによって、空の柔らかい青とミルトス(ギンバイカ)とオレンジの葉の光沢のある草色を暗くし、また花や果物の明るい色合いを薄暗くした今日でさえ、サンドロの「春(プリマヴェーラ)」は、詩人であり画家であるサンドロの魂に現れた最も幻想的な情景の一つである。若いフィレンツェの巨匠の作品の美しさは、カステッロの美しい庭園でその喜びの春の時間に遭遇した人文主義者の称賛をどれほど呼び起こしたことか!しかし、悲劇的な運命は、若さと愛の夢の上に影を落としていた。

| |

Quant'è bella giovinezza,

|

うるわしき若さも

| |

|

CHAPTER VII

So, in the words of Lorenzo's Carnival hymn, sang the chorus of youths in Greek costumes, as the pageant of Bacchus and Ariadne was borne on a triumphal car from the doors of the Medici palace, while troops of white-robed maidens, crowned with flowers, danced merrily on the Piazza di Santa Trinita and mingled their songs with the voices of the young men, to the music of viols and flutes. Giuliano himself joined in the mirth, and the Magnifico, with Poliziano at his side, looked on from the steps of his house at the corner, as the gay revellers passed before him in procession, all unmindful of the prophetic ring in the light refrain of their song, telling them how soon youth and joy must pass away. Within a year of Giuliano's triumphal Tournament, the "bella Simonetta" was no more, and exactly two years later, before Poliziano had finished the second book of his "Giostra", Giuliano himself, the darling of the Florentines, was murdered by the Pazzi conspirators on Sunday, the 26th of April, 1478. Poliziano broke off his poem to tell in sterner prose the dark story of the plot that brought his hero's life to this sharp and sudden close, and Sandro turned from painting visions of beautiful nymphs and the joyous spring-time, to record the names and effigies of the traitors, on the walls of the Palazzo Pubblico.

|

第七章

そうして、ロレンツォのカーニバル賛美の歌を、ギリシアの衣装で若者が合唱して歌い、バッカスとアリアドネが勝利の車に乗り、メディチ宮殿の扉から行列になって出て行ったとき、白い衣装を着た少女たちは花の冠を戴き、隊を組んで進み、聖トリニータ広場で陽気に踊り、ビオールとフルートの音楽に沿って、若い男性の声と歌を合わせた。ジュリアーノ自身は歓喜の催しに参加し、マニィフィコは、彼の側にポリツィアーノを従え、メディチ宮殿の角にある階段から、陽気な酔っ払いたちが行列をなし、彼の前を行進するのを見ていた。その歌は、明るい反復にある預言的な意味にはみな気がつかず、青春と喜びがいかに早く消えてゆかねばならぬかを伝えている。騎馬試合にジュリアーノが勝利してから一年以内に、「美しきシモネッタ」は早くも亡くなった。そしてちょうど二年後、ポリツィアーノがその「騎馬試合(ジオストラ)」の第二巻を完成させる前に、フィレンツェの人気者、ジュリアーノ自身が、1478年4月26日の日曜日にパッツィ家の陰謀で殺害された。ポリツィアーノは、ジュリアーノに突然で凄惨な死をもたらした陰謀の暗い筋書きを断固たる文体で語るために、詩作の継続をやめた。サンドロは美しい乙女や楽しい春の時の情景の絵画製作から、今度は庁舎の壁面に裏切り者の名前を記録しその末路の肖像を描くことになった。

|

CHAPTER VIII∧ 1478 - 1480

Conspiracy of the Pazzi.

|

第八章∧

1478 - 1480

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

THE conspiracy of the Pazzi sent a thrill of horror through Florence. The plot had been hatched in Rome by the Pope's nephew Girolamo Riario, and Francesco Pazzi. Another kinsman of his Holiness, the young Cardinal Raffaelle Riario, a boy of sixteen, was present as the honoured guest of the Medici brothers and was with them in the Duomo at Mass, when the bloody deed was done. The Archbishop of Pisa, Francesco Salviati, took an active part in the conspiracy, and the Pazzi family was closely connected with the rival house of Medici, Guglielmo de' Pazzi being the husband of Lorenzo's sister Bianca. Two priests actually made the attempt upon Lorenzo's life, and to crown all, the murder took place at the most solemn moment of the mass. Giuliano fell dead on the steps of the choir, pierced with nineteen wounds by the daggers of the traitors. One of them, Francesco Pazzi, was conversing in the most familiar manner with him, as they walked up the nave of the great church together, and threw his arm round the waist of the murdered man, to ascertain that he wore no armour under his doublet. Lorenzo himself narrowly escaped the same fate, and was only saved by his own presence of mind and the courage and devotion of his friends. One of them, Francesco Nori, was stabbed through the heart in his efforts to save the Magnifico's life, and the assassin's dagger grazed Lorenzo's neck as, running in front of the high altar, he took refuge in the Sacristy, where Poliziano and his companions closed Luca della Robbia's bronze doors in the face of his pursuers. "The holiest places of the Duomo ran with blood. Nothing but noise and shouting," wrote an eye-witness, Filippo Strozzi, "could be heard in the church. A general panic seized all who were present. One fled here, the other there," while the terror-stricken boy Cardinal clung to the steps of the altar and protested his innocence."

|

第八章

パッツィ家の陰謀はフィレンツェ中にぞっとするような恐怖を広げた。陰謀の策略は法王の甥ジロラモ・リアリオとフランシスコ・パッツィによってローマで立てられた。ローマ法王の別の親族、若い枢機卿ラファエーレ・リアリオ、当時16歳の少年は、メディチ兄弟の名誉ある賓客として出席し、血まみれの行為が行われたときに、ミサが行われたドウオモで彼らと一緒にいた。ピサの大司教、フランチェスコ・サルヴィアティは、陰謀に積極的に参加した。パッツィ家は競争相手のメディチ家と密接に結ばれていた。グリエルモ・デ・パッツィはロレンツォの姉ビアンカの夫である。二人の司祭は、実際にロレンツォの命を狙い、何度も狙った挙句の果てに、殺害の企てはミサの最も厳粛な瞬間に行われた。ジュリアーノは聖歌隊席の階段で死亡したが、裏切り者の短剣によって突き刺され十九箇所もの傷を負っていた。首謀者の一人フランチェスコ・パッツィは、これから殺そうとする相手の男と大聖堂の真ん中の通路を並んで歩く時に、胴着の下に鎧を着ていないことを確かめるために、親しそうに話しかけながら、相手の男の胴の周りに腕をまわした。ロレンツォ自身も危ういところで同じ運命を逃れ、自身の平静さと友人たちの勇気と献身によってやっとのところで救われた。そのうちの一人フランチェスコ・ノーリは、マニィフィコの命を救うおうと、一瞬自らを盾にしたために心臓を突き刺された。さらに暗殺者の短剣は、ロレンツォの首をかすめた。彼は高祭壇の前を走って、聖具室に逃げ込んだ。そこでポリツィアーノやその同志たちが追っ手を避けるためにルカ・デッラ・ロッビア作の青銅の扉を閉めた。目撃者のフィリッポ・ストロッツィは、「ドウオモの最も聖なる場所には血が流れた。騒音と叫び声のほかには何も教会で聞こえなかった。そこにいた人々はみなパニックになった。恐怖におびえた枢機卿の少年は祭壇の階段に這いつくばって、自分の無実を主張していた」と書いた。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

But the Florentines rallied loyally round Lorenzo, and crowds surrounded the palace to which he had been borne in safety with shouts of "Palle, palle!" Giuliano's murder was avenged with terrible promptitude. Francesco Pazzi, the Archbishop of Pisa, and two of his kinsmen were hung that very day from the windows of the Palazzo Pubblico. Jacopo Pazzi, the head of the family, managed to escape from the city, but was caught hiding in the neighbourhood and given up to justice by a young peasant, and was hanged, together with his brother Renato. The guilty priests were discovered hidden in the Badia and dragged out to torture and death. Bernardo Bandini Baroncelli, who was Giuliano's actual assassin, escaped to Constantinople, but was surrendered a year later by order of the Sultan, and was hanged from the Palazzo. "He was a bad, bold man," writes Poliziano, "who knew no fear, and was mixed up in every kind of wickedness. And he was the first who stabbed Giuliano in the heart with a dagger. Then not content with having murdered Giuliano, he hurried towards Lorenzo, who was able to escape into the Sacristy with a few followers, upon which Bandini ran his sword through Francesco Nori, an able man who was one of the Medici's chief agents." More than seventy victims, among whom were several innocent kinsmen and servants of the Pazzi, were put to death in all, and the walls of the Palazzo were lined with corpses.

|

第八章

しかし、フィレンツェの人々は忠義にもとづきロレンツォのもとに結集し、群衆は彼が安全確保のために戻っていたメディチ宮殿(本邸)を「球、球(訳者注:パルレの繰り返しは6つのボールを含むメディチの紋章を指す)」の叫び声で囲んだ。ジュリアーノの殺害には恐ろしいほど迅速に仕返しが行われた。ピサ大司教のフランチェスコ・サルヴィアティとその親近者二人は、すぐに市庁舎(シニョーリア、またはパラッツォ・パブリシコ)の窓から吊り下げられた。パッツィ家の長老ヤコポ・パッツィは街から逃げ出したが、近辺に隠れているところを見つけられ、若い農民により正義に服し、弟のレナトと共に一緒に吊された。悪事を働いた司祭たちはバディアに隠れていたのを発見され、引きずりまわしの拷問を受け死亡した。ジュリアーノを実際に暗殺したベルナルド・バンディーニ・バルンチェリは、コンスタンティノープルに逃げたが、一年後にはスルタンの命令で降伏し、市庁舎から吊り下げられた。ポリツィアーノは「彼は悪で、大胆な男だった。恐れ知らずで、あらゆる種類の邪悪に染まっていた。そして、彼は、最初にジュリアーノの心臓を短剣で刺した男であった。その後、ジュリアーノの殺害では満足せず、彼はロレンツォのところへ急いだ。バンディーニはメディチ家の首席代理人の一人である有能なフランチェスコ・ノーリを剣で突き抜いたが、ロレンツォは、幾人かの同志と一緒に聖具室に逃げこんだ」と書いた。七十人以上の犠牲者が出たが、その中には何人かの罪のない近親者やパッツィ家の召使が死んでおり、市庁舎の壁には死体が並んでいた。

| |

|

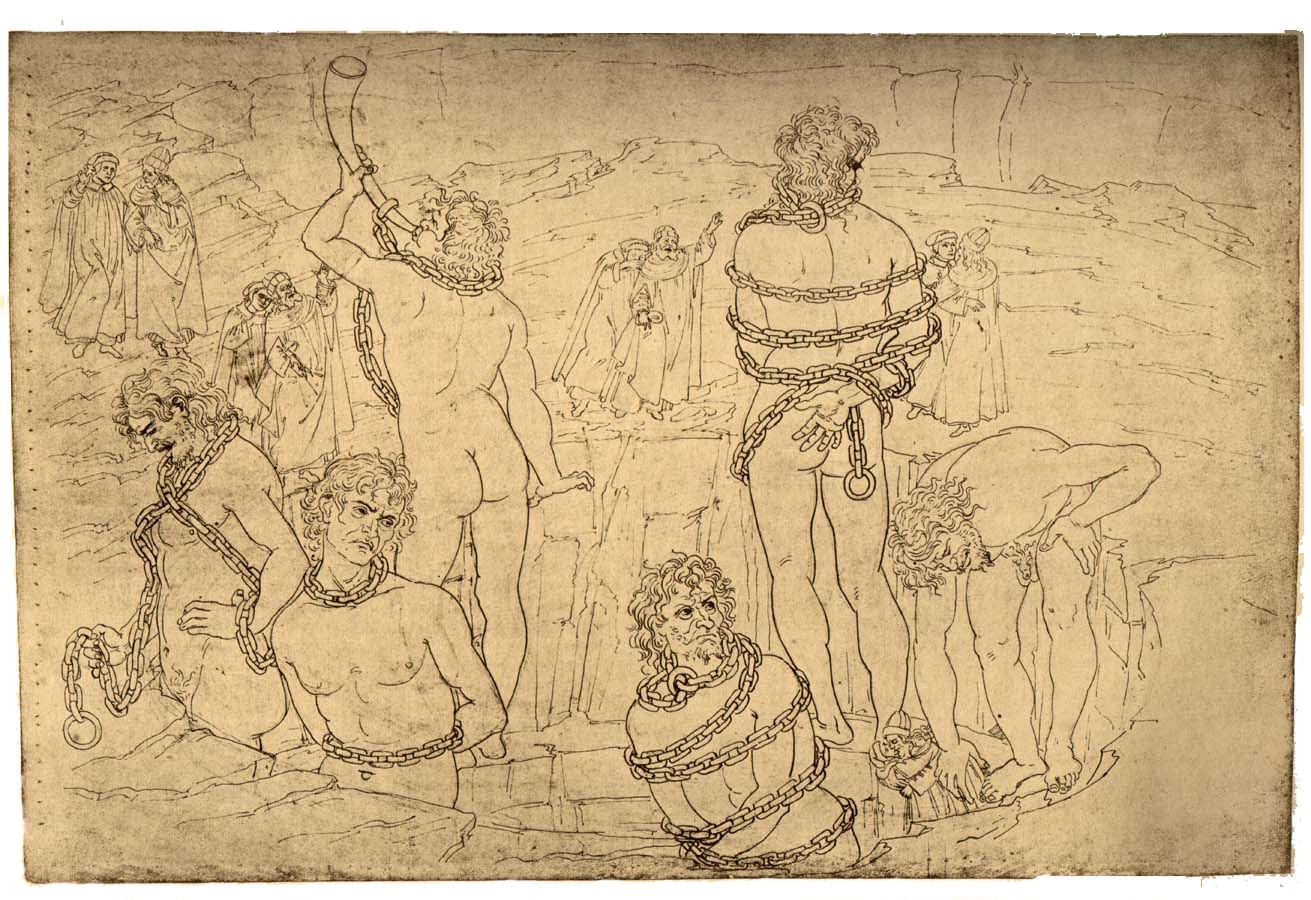

CHAPTER VIII

It was then that Sandro Botticelli was employed by the Signory to paint the effigies of the chief conspirators upon the exterior of the palace walls. "In 1478," writes the Anonimo Gaddiano, "on the facade where was the Bargello, above the Dogana, he painted Messer Jacopo, Francesco and Renato de' Pazzi, and Monsignor Francesco Salviati, Archbishop of Pisa, and two Jacopo Salviatis, one the brother, the other the kinsman of the said Messer Francesco, and Bernardo Bandini, hung by the neck, and Napoleone Francesi, hung by one foot, who all conspired against Giuliano and Lorenzo de' Medici. And at the foot of their effigies Lorenzo placed epitaphs, and the one on Bandini runs thus:

|

第八章

サンドロ・ボッティチェリが陰謀の中心人物たちの肖像をポデスタ宮の壁の外面に描くことを委嘱されたのはこのときであった。「アノニモ」・ガッディアーノは、「1478年に、税関の上のバルジェロ宮があった正面外壁に、ボッティチェリは、長老ヤコポ、フランチェスコとレナート・デ・パッツィ、そしてピサ大司教フランチェスコ・サルヴィアティ、二人のヤコポ・サルヴィアティとその弟、フランチェスコの近親者、ベルナルド・バンディーニの絞首刑、ナポレオーネ・フランチェシの片足吊りの刑を描いた。これらの人物はいずれもジュリアーノとロレンツォの暗殺の陰謀に関わった。そしてそれらの肖像の下にロレンツォはそれぞれ碑文を置いた。バンディーニのところには次の碑文がある。

| |

Son Bernardo Bandini, un nuovo Giuda.

|

私はベルナルド・バンディーニ。ユダの生まれ変わりだ。

| |

|

This description of Bandini, as a traitor and murderer in church, shows how much the horror of the crime was heightened by the fact that it was perpetrated in the sanctuary. Napoleone Francesi, whom Sandro painted, the Anonimo tells us, hanging by one foot, was represented in this manner, because he alone among the conspirators succeeded in escaping safely, and, more fortunate than Bandini, was never captured.

|

教会内での事件の犯人、裏切り者、殺人者としての、バンディーニについての、この碑文は、犯罪が聖域で犯されたという事実によってその恐怖がいかに増したかを示している。サンドロが描いたナポレオーネ・フランチェシは、「アノニモ」によれば、片足吊りの刑に処されたことになっているが、この男はバンディーニよりも悪運が強く、陰謀に加わった者たちのなかで唯一、のうのうと逃げおおせたのだった。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

The selection of Sandro for this office is another proof of his close connection with the Medici and of the high favour in which he stood with Lorenzo at this period. The Council of Outlawry, from whom he received the commission, paid him forty gold florins for executing the task in the month of July, 1478, so that we may conclude he spent about two months on the work. According to Vasari, who, however, ascribes the painting of the effigies of the Pazzi conspirators to Andrea del Castagno, the work was executed in a marvellous manner. "It would indeed be impossible," he writes, "to describe the art and judgement which was shown in the personages here portrayed mostly taken from life and hung in strange attitudes of the most varied and beautiful description."

|

第八章

この仕事にサンドロが選ばれたことは、メディチ家との密接な関係と、彼がこの時期にロレンツォから高く評価されていたことのもう一つの証拠でもある。法務委員会からサンドロはこの仕事を依頼されたのだが、この委員会は1478年7月にその仕事のために40フローリンをサンドロに支払ったことから、我々はサンドロがこの仕事に約二ヶ月を要したと結論づけることができる。パッツィ家の共謀者の肖像はアンドレア・デル・カスターニョが描いたものだとするヴァザーリも、この作品は大変よくできていると評価している。「それは死の姿を描かれ、ほとんど命を取られ、最も多様で美しく描かれた奇妙な姿勢で吊るされた人物に示された芸術と審判を描写することは確かに不可能だっただろう」とヴァザーリは書いている。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

Another curious thing which may be mentioned, in connection with this grim task that was assigned to Botticelli, is that his friend Leonardo has left us a drawing of Bandini's execution, which was taken on the 29th of December, 1479, when the criminal was hanged, after being given up by the Sultan. The keen interest and close attention with which the artist has followed the death-agony of the wretched criminal, is characteristic of the master who used to attend executions and dissect corpses in Milan. The body, in its loose garments, is seen hanging at the end of a rope with the head bent forward, the arms tied behind the back, and in the margin of the framing we read the following notes describing Bandini's clothes: "Small tan-coloured cap, black satin doublet, blue mantle lined with fox, black hose." These details seem to imply that the drawing, which is now in M. Bonnat's collection, originally served as a sketch for a more important work. Perhaps Leonardo may have been employed to paint the effigy of Bandini, by the side of the conspirators whom Botticelli had already depicted on the walls of the Bargello.

|

第八章

ボッティチェリに任されたこの厄介な仕事に関連して言及されるであろうもう一つの別の奇異な事実は、サンドロの友人レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチが、トルコのスルタンによって送還され、1479年12月29日にフレンツェで絞首刑になった犯罪者バンディーニのスケッチを我々に残していることだ。レオナルドはミラノで死刑執行に立会い、遺体解剖を何度もしていたのだが、そうした画家としての特性が、卑劣な犯罪者の死の苦しみを、鋭い関心と細心の注意をもって描かせている。ゆるい衣服をまとった身体は、縄の端にぶら下がって見え、頭が前に曲がっていて、腕が背中で縛られている、スケッチの余白に、バンディーニの衣服を説明した次の記述がある:「小さな黄褐色の帽子、黒サテンの胴着、キツネ、黒馬の毛の線が並んだ青い上衣」これらの詳細な記述は、現在、ボナ美術館の所蔵のスケッチが、もともとは、より重要な作業のスケッチとして描かれたことを暗示しているようだ。おそらくレオナルドはボッティチェリがバルジェッロの壁にすでに描きあげていた共謀者の絵画のそばで、バンディーニの肖像を描くよう依頼されていたのかもしれない。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

During the troubled times that followed the death of Giuliano and the rising of the Pazzi, we hear of no more commissions for pictures. Florence was threatened by enemies on every side, and all Lorenzo's courage and diplomacy were needed to suppress factions at home, and to avert the open and covert attacks by which Pope Sixtus endeavoured to effect his downfall. But when this critical moment in his career was over, and the security of the State and his own supremacy was assured, the Magnifico once more employed Sandro to work for him.

|

第八章

パッツィ家の反乱とジュリアーノの死に続く苦難の時代には、絵画製作の依頼はまったく途絶えたようだ。フィレンツェはあらゆる方向の敵に脅かされていた。ロレンツォは自らの全ての勇気と外交力を振り絞って、国内の対立を抑え、法王シクストゥスがロレンツォの失脚を成し遂げようとやっきになり、仕掛けてきた公然・非公然の攻撃を避けることが必要だった。しかし、なんとかこの重大な危機を乗り越え、国家の安全と彼自身の覇権が確保できたときには、マニュフィコはサンドロを彼のためにもう一度働かせた。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

In the spring of 1480, Lorenzo returned in safety from his perilous mission to the court of Naples. This bold step had been crowned with complete success. After three months' parleying, King Ferrante had finally signed a treaty with the Florentine republic, and Lorenzo was able to set sail for Pisa, taking with him as a parting gift from the old king, a fine horse which he received with the remark "that a messenger of joyful news ought to be well mounted." When he reached Florence he met with the most enthusiastic reception. "The whole city," writes Guicciardini, "went out to welcome him, and hailed his coming with the greatest joy, since he brought with him peace and the assurance of the preservation of the State." His faithful friend Poliziano celebrated the occasion in a new poem, expressing his joy at the sight of Lorenzo's face and his longing to clasp his right hand and bid him welcome to his home:

|

第八章

1480年の春、ロレンツォはナポリ宮廷での危険な任務から無事に帰ってきた。ロレンツォ自身が数人の側近だけを伴って、ナポリに乗り込むという、この大胆な措置は、完全な成功を収た。三ヶ月にわたる談判の後、ナポリ王フェルディナンド(訳者注:フェランテとも呼ばれる)はフィレンツェ共和国との条約に遂に署名をした。ロレンツォはピサに向けて出帆することができた。親しくなった王からは別れに当たって見事な馬の贈り物を受けた。ロレンツォはこの贈り物を受けるさいに、「喜ばしい知らせの使者は良い馬に乗らなくては」と礼を述べた。彼がフィレンツェに帰還したとき、かつてないほどの熱狂的な歓迎を受けた。歴史家グイチャルディーニは、「全市民が、平和と国家の安全の保証を持ち帰ってきたのロレンツォを歓迎するために街に出て、大いに喜んで彼の帰還を歓呼して迎えた」と書いている。彼の忠実な友人ポリツィアーノは、ロレンツォの顔を見たときの喜びと、彼の右手を握りしめて故郷への帰還を歓迎したいという思いを、新しい詩を作って表現した:

| |

O ego quam cupio reducis contingere dextram

|

ああ、我、君の右手に触れたし

| |

|

The poet gives an animated account of the scene that day at the palace of Via Larga, of the crowds which filled the halls and of his own vain endeavour to press through the joyful throng and 人に the hero of the hour, whom he sees from afar, with smiling countenance, greeting his friends and thanking them with words and smiles and hands. But since he cannot greet him in person, he sends Lorenzo his verses to hail him on this auspicious day and bear witness to his servant's love and joy:

|

詩人は、その日、ラルガ街の宮殿での、広間を満たした群衆やそして時の人に挨拶をしようと嬉しそうな群衆をかき分けて進もうとする詩人自身の虚しい努力を生き生きと語る。時の人は遠くからしか見えなかったが、笑顔で、友人と言葉や笑顔と握手で挨拶し礼を言っていた。しかし、詩人は直接時の人に挨拶ができないので、かわりに、このめでたい日にロレンツォを讃える詩を、しもべの愛と喜びの証しとして、送る:

| |

Ite, mei versus, Medicique haec dicite nostra:

|

行くがいい、私の歌よ、メディチのもとへ、最高の友への挨拶として

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

It was then that the Magnifico, desirous to commemorate the restoration of peace and his own triumphant return, employed Botticelli to paint the famous picture of Pallas subduing the Centaur which was discovered some ten years ago, in a dark corner of the Pitti Palace.  The only mention of this painting in contemporary records is to be found in an inventory of the contents of the palace in Via Larga that was taken on the 7th of October, 1516. Six months before that date Giuliano de' Medici, the Magnifico's son, had died at Fiesole. His only surviving brother, Giovanni, was the reigning Pope, Leo X, and his nephew, Piero's son Lorenzo, had been proclaimed Duke of Urbino. The only Medici left in Florence, were the representatives of the younger branch of the house, Piero, the son of Botticelli's patron, Lorenzo di Piero Francesco, and his first cousin, Giovanni delle bande nere the son of Caterina Sforza. A division of the family property was made between them, and in the list of pictures here mentioned we find the following entry: "In the second room on the ground floor, a figure of Minerva and a Centaur." The only mention of this painting in contemporary records is to be found in an inventory of the contents of the palace in Via Larga that was taken on the 7th of October, 1516. Six months before that date Giuliano de' Medici, the Magnifico's son, had died at Fiesole. His only surviving brother, Giovanni, was the reigning Pope, Leo X, and his nephew, Piero's son Lorenzo, had been proclaimed Duke of Urbino. The only Medici left in Florence, were the representatives of the younger branch of the house, Piero, the son of Botticelli's patron, Lorenzo di Piero Francesco, and his first cousin, Giovanni delle bande nere the son of Caterina Sforza. A division of the family property was made between them, and in the list of pictures here mentioned we find the following entry: "In the second room on the ground floor, a figure of Minerva and a Centaur."

|

第八章

それは、マニフィコが、平和の回復と自身の凱旋を記念したいと思い、ボッティチェリに、現在では非常に有名になった「パラスとケンタウロス」を描かせることにしたのは、このときである。 この「パラスとケンタウロス」は、約十年前(1897年ころ)にピッティ宮の暗い人目につかない場所で発見された作品である。この作品の唯一の言及は、1516年10月7日に引き取ったと、ラルガ街のメディチ宮殿の所蔵物の台帳に当時の記録があった。その日の半年前、マニフィコの息子ジュリアーノ・デ・メディチは、フィエゾレで死亡している。その唯一の生き残りの兄弟、ジョヴァンニは、当時、法王レオ十世で、その甥、ピエロの息子ロレンツォはウルビーノ公と宣されていた。フィレンツェに残された唯一のメディチの家系が、その若い分家の当主の、ピエロで、すなわちボッティチェリのパトロンであるロレンツォ・ディ・ピエロフランチェスコである。そしてその最初のいとこ、カテリーナ・スフォルツァの息子ジョヴァンニ・デッレ・バンデ・ネーレ(訳者注:「バンデ・ネーレ」は黒帯の意)であった。一家の財産の分割は、家族間で決められた。絵画作品の一覧の中に、我々は次の記載を見つけた:「一階の二番目の部屋、『ミネルバとケンタウロスの姿』」 この「パラスとケンタウロス」は、約十年前(1897年ころ)にピッティ宮の暗い人目につかない場所で発見された作品である。この作品の唯一の言及は、1516年10月7日に引き取ったと、ラルガ街のメディチ宮殿の所蔵物の台帳に当時の記録があった。その日の半年前、マニフィコの息子ジュリアーノ・デ・メディチは、フィエゾレで死亡している。その唯一の生き残りの兄弟、ジョヴァンニは、当時、法王レオ十世で、その甥、ピエロの息子ロレンツォはウルビーノ公と宣されていた。フィレンツェに残された唯一のメディチの家系が、その若い分家の当主の、ピエロで、すなわちボッティチェリのパトロンであるロレンツォ・ディ・ピエロフランチェスコである。そしてその最初のいとこ、カテリーナ・スフォルツァの息子ジョヴァンニ・デッレ・バンデ・ネーレ(訳者注:「バンデ・ネーレ」は黒帯の意)であった。一家の財産の分割は、家族間で決められた。絵画作品の一覧の中に、我々は次の記載を見つけた:「一階の二番目の部屋、『ミネルバとケンタウロスの姿』」

| |

|

In another inventory, taken at a slightly later date, this entry is repeated as follows: "In the second room, by the side of the hall on the ground floor, a Minerva and Centaur on canvas, with a panel behind it."

|

それほど離れていない後日に調査されたもう一つの台帳に、同様の記載がある:「一階の広間の隣の第二の部屋、板で裏打ちされたカンバスに描かれた『ミネルバとケンタウルス』」

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

This description is perfectly accurate, and the newly-discovered picture now in the Pitti Palace is painted on canvas, which Botticelli also employed for his Birth of Venus in the Uffizi, a work probably executed about the same time. The Pallas passed into the Pitti Gallery together with most of the Grand Ducal collection, towards the end of the eighteenth century, and was engraved in Frassinetti's "Galleria Pitti illustrata", published in 1842. The editor of that work describes the work in question as an "An Allegory by Sandro Botticelli", which seemed to be connected with Lorenzo il Magnifico, since it bore his device of the triple ring, but the exact significance of which it was impossible to explain. Fourteen years later, on the marriage of the Archduke Ferdinand of Lorraine, some alterations were made in the Pitti Gallery, and Botticelli's Pallas was removed with some other pictures to a storeroom in the palace, where its very existence was forgotten. It was only in 1895, that an English connoisseur, Mr. Spence, who happened to be paying a visit to the Duke of Aosta, caught sight of the Pallas in a dark ante-room of the private apartments reserved for royal use, and recognized it as a work of Botticelli.

|

第八章

この説明は正確であり、ピッティ宮殿で新しく発見された絵画はカンバスに描かれている。ボッティチェリはおそらく同じ時期に製作したウフィッツィ美術館所蔵の「ヴィーナスの誕生」にもカンバスを使った。「パラス」は、18世紀末にかけて、大公国コレクションの大部分と一緒にピッティ美術館に収蔵された。1842年に出版された「ピッティ美術館所蔵画集」に彫版で印刷された。この画集の編集者は、問題の作品について、「サンドロ・ボッティチェリの寓意」として記しているが、ロレンツォ・イル・マニフィコの図柄である三重の輪が描きこまれていることから、ロレンツォと結びつきがあると考えられた。しかし、そのことの正確な意味は説明ができなかった。14年後、ロレーヌ大公フェルディナンドの結婚で、ピッティ美術館でいくつかの改修が行われ、ボッティチェリの「パラス」は、宮殿の倉庫にいくつかの他の作品と共に移された。以降、その倉庫の存在自体が忘れられてしまった。アオスタ公を訪問することになっていた英国の鑑定家スペンスは、フィレンツェで王室御用達のために確保された居住区画の暗い控えの間で「パラス」を見つけ、そしてそれがボッティチェリの作品であると認識したのは、つい近年の1895年であった。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

Although this painting is not mentioned by Vasari or any contemporary writer of the Laurentian age, it is clear that we have here an allegory of Lorenzo de' Medici's victory over his enemies, and the establishment of his wise and beneficent rule. As Poliziano's courtly verse records the most glorious moment in the Magnifico's life, so Botticelli's painting remains a lasting memorial of Lorenzo's triumph and the disastrous fate of the Pazzi conspirators. Art and poetry had already associated the goddess Pallas with the house of Medici. The muse of Poliziano and the brush of Sandro had taught the Florentines to see in the Greek goddess the protectress of Lorenzo and Giuliano, and the guardian of their family. On the other hand, the Centaur had been held to be the symbol of political strife and disorder since the days of Plutarch. Giotto introduces a Centaur as a type of rebellion and crime into his fresco of Obedience at Assisi, and Dante speaks of the Centaurs as accursed creatures in his "Purgatorio".

|

第八章

この作品はヴァザーリやロレンツォの時代の著述家によって言及されていないが、ロレンツォ・デ・メディチが敵に勝利したこと、そしてその賢明で慈悲深い統治が確立されたことの寓意がここにあることは明らかである。ポリツィアーノの宮廷風の詩はマニフィコの人生で最も栄光の瞬間を記録し、ボッティチェリの絵画は、ロレンツォの勝利とパッツィ家の共謀者の悲惨な運命の永続的な記念碑として残る。芸術と詩はすでに女神パラスをメディチ家に結び付けていた。ポリツィアーノの詩才とサンドロの筆は、フィレンツェの人々に、ロレンツォとジュリアーノに、ギリシャの守護女神とその家族の守護者を見るように導いていた。一方、ケンタウルスはプルタルコス(訳者注:プルータク英雄伝で知られる)の時代から政治的な闘争と無秩序の象徴とされてきた。ジオットはアッシジの「服従」のフレスコ画に反逆と犯罪の見本としてケンタウロスを描き、ダンテは「神曲・煉獄編」の呪われた生き物としてケンタウロスを語る。

| |

|

In this case, the Centaur not only appears as a common emblem of crime and folly, but fitly represents the Pazzi, whose name literally signifies "fools".

|

この場合、ケンタウロスは犯罪と愚行の共通の象徴として現れるだけでなく、パッツィ家をぴったりと象徴している。なぜなら、その名パッツィ、pazziは文字通りイタリア語で「狂気」を意味するのだ。(訳者注:元の英文ではfoolsで、役は「愚か者」となるが、イタリア語のpazziを訳すと「狂気」となる。)

| |

CHAPTER VIII

Nothing can be simpler than the composition. Pallas, a tall and stately figure, bearing the Medusa shield on her back, and armed with a massive halberd, stands before us as if she had just alighted upon the earth, and seizes the Centaur by the forelock. Her white robe is embroidered with the triple diamond ring that was the favourite device of the Medici, and the graceful olive bough wreathed about her brows and trailing over her breast and arms, are symbols of the good tidings of peace which Lorenzo had brought back with him from Naples. This Centaur with the shaggy locks reminds us of the painting by the Greek artist Zeuxis, which Lucian describes. But he is no monster of vice and ugliness. On the contrary, his venerable figure and aged face seem to plead for mercy, as he cowers before this triumphant daughter of the gods, who looks down upon her captive in all the might of divine youth and beauty. Behind her we catch a glimpse of distant hills and seas, that may be intended to represent the Bay of Naples, with the ship which bore Lorenzo homewards sailing across its waters.

|

第八章

構図はこれ以上簡単になることはできないほどだ。パラスは背が高く、堂々とした姿であり、背中にメドゥーサの盾を背負い、そして巨大な斧槍で武装している。彼女はちょうど地上に降りて、ケンタウルスの前髪を捕捉したかのように我々の前に立つ。彼女の白衣は、メディチ家の好みの三重のダイヤの指輪文様で刺繍され、そして優雅なオリーブの枝が彼女の額を輪になって飾り、胸や腕の上枝は伸びている。このことは、ロレンツォがナポリから持ち帰った平和の良い知らせの象徴である。この毛深い髪が房になったケンタウルスは、ルキアノスが記したギリシャの画家ゼウクシスが描いた作品を思い出させてくれる。しかし、ケンタウルスは邪悪で醜怪な怪物ではない。それどころか、聖なる若さと美しさのすべてをまとって捕ええた捕虜を見下す、この勝ち誇った神々の娘の前で、ケンタウルスは、縮こまりながら、その由緒ある姿と老いた顔で、慈悲を嘆願しているようだ。パラスの背後には、遠くの丘や海が垣間見える。それはナポリ湾を示しているようだ。船には海を越えて帰還するロレンツォが乗船しているのだ。

| |

|

CHAPTER VIII

Both the types and general style of the picture confirm the supposition that it was painted in the year 1480, some time after the Primavera, but certainly before the Birth of Venus. The figure of Pallas resembles the Fortezza and the figure of Venus in the Allegory of Spring. But although her form still retains the prominent curve of the line of hip, which is a curious feature of Sandro's early frescoes, the signs of the Pollaiuoli's influence are less marked than in these last-named works. The gentle, half-pitying expression on the face of Pallas, and the decorative pattern of the olive foliage, are full of charm, and the painter's scheme of colour is nowhere more pleasing and harmonious than in this composition. The mantle falling over the white robes of the goddess is of a rich green; the sandals on her feet are of orange hue, and her bright locks of red-gold stream on the breeze, in the soft, rippling waves commended by Alberti. On the left, a mass of gray shelving rocks represents the cavern which is the Centaur's home, and forms a striking background to the group. So the painter once more proved that poetic imagination can gild the dullest theme with light, and transform even a political cartoon into a dream of beauty.

|

第八章

作品の様式も全体的な表現法のどちらもが、この作品が「春(プリマヴェーラ)」のあと、しかし、確かに「ヴィーナスの誕生」以前の1480年に描かれたものだという推定を強固にさせる。パラスの姿は、「剛毅(フォルテッツィア)」や「春の寓意(訳者注:春『プリマヴェーラ』の意)」のヴィーナスの姿に似ている。彼女の姿態はサンドロの初期のフレスコ画で特徴的な腰の際立つ曲線を保持しているが、ポライウォーロ兄弟の影響の兆候は「春(プリマヴェーラ)に比べてあまり認められない。パラスの顔の優しく、半ば哀れむような表情、及びオリーブの葉の装飾的模様は、魅力に満ちている。この画家の色彩の扱い方は、この作品の構成におけるよりも、心地よく調和のとれたものは他にない。女神の白い衣の上に重なる上衣は、豊かな緑である。彼女の足の履物は、オレンジ色の色相のものであり、そして明るい赤みを帯びた金色の髪が、アルベルティが言うように、そよ風の柔らかいさざなみのなかで、たなびいている。左側の灰色の棚のようになっている岩石の塊は、ケンタウルスの住処である洞窟を表し、印象的な背景を形成している。そうして、画家はいま一度、詩的想像力が最も退屈な主題をも光をあて見事なものにできることを、さらに政治風刺画でさえもを美の夢の中に変えることができることを証明した。

| |

|

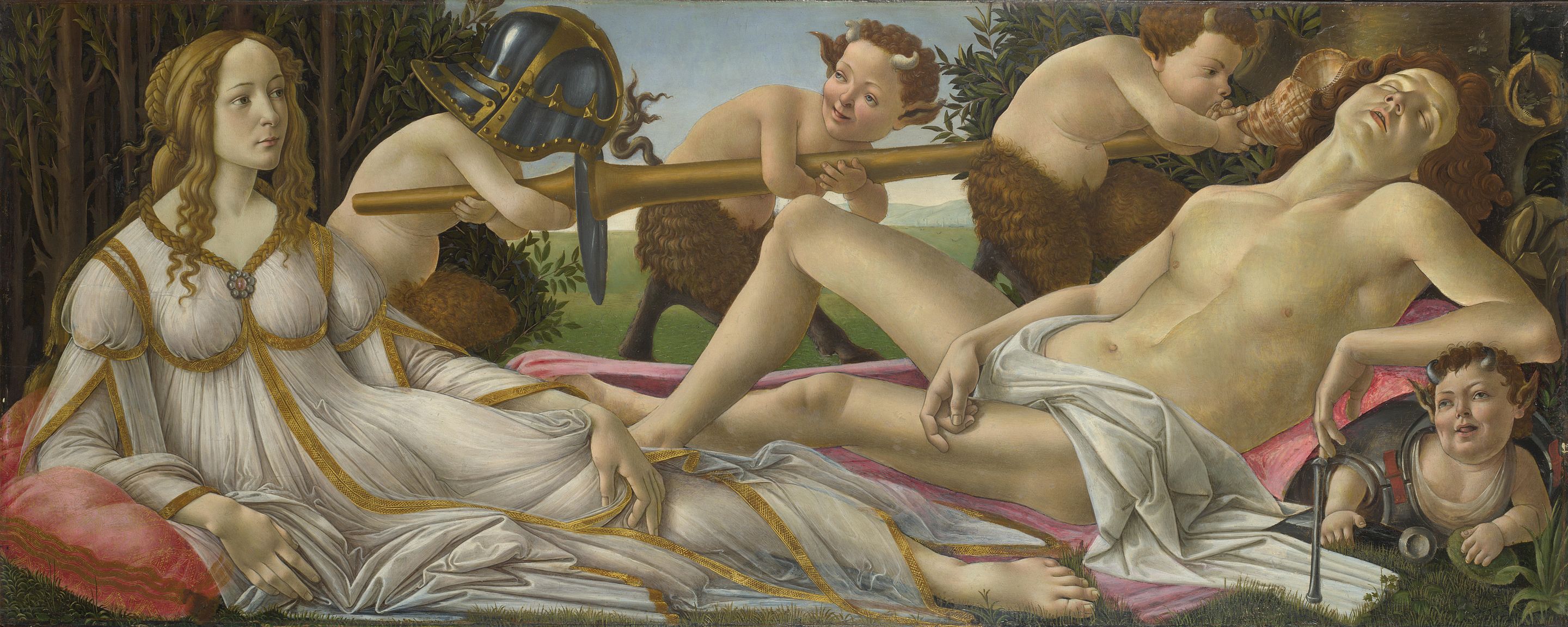

We have neither historical information nor documentary evidence to guide us in determining the precise date of the two other mythical subjects by Sandro's hand, which are still in existence. One is the Birth of Venus which Vasari mentions, together with the Primnavera, as being in the Grand Duke Cosimo's villa of Castello, and which came with the Grand Ducal collection into the Uffizi. The other is the long, narrow panel which goes by the name of Mars and Venus in the National Gallery.

|

今存在しているサンドロの手による神話を主題にした他の二つ作品の正確な完成日付を決定するのに必要な、歴史上の情報も文献上の証拠も我々は持っていない。ヴァザーリによれば、その一つは「ヴィーナスの誕生」である。「春(プリマヴェーラ)」と一緒にコスモ大公邸のカスティーヨ邸にあったもので、現在はグラン・デュカル・コレクションとしてウフィツィ美術館に入っている。もう一つは、ロンドン・ナショナル・ギャラリー所蔵の上下は小さく横長(訳者注:69cm x 173.5cm)の板絵の「ヴィーナスとマルス」である。

| |

|

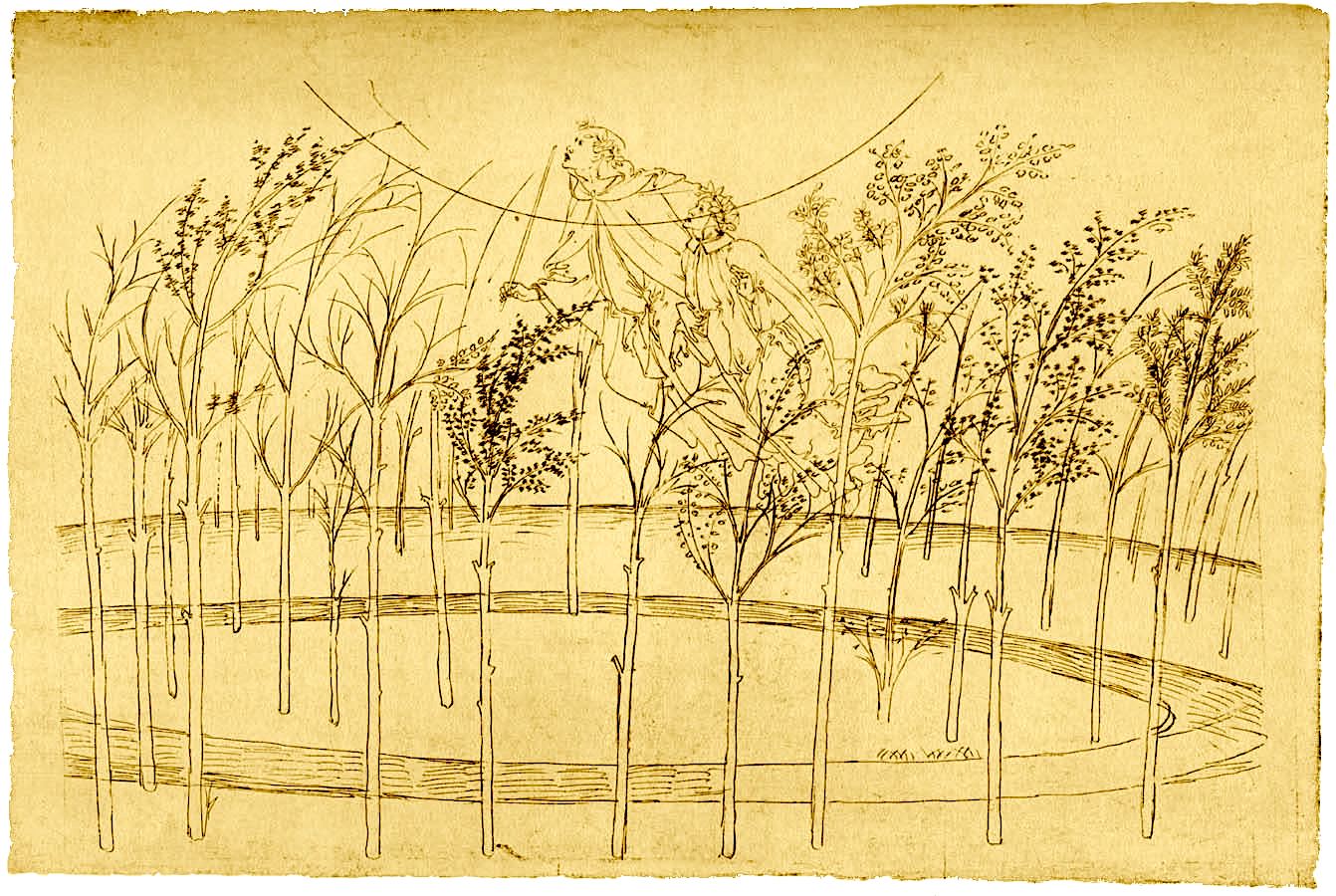

CHAPTER VIII

The subject of the former picture, as we have already seen in the case of the Primavera was evidently derived from Poliziano's poem of Giuliano's Giostra. In a passage adapted from one of the Homeric hymns, the poet describes the birth of Venus. Among the sculptured reliefs which adorned the portals of the palace of Venus in the enchanted isle of Cyprus, he sees the new-born Aphrodite, a maiden with a divine face, gently wafted by the soft breath of the Zephyr on the white foam of the Aegean waves, towards the flowery shore:

|

第八章

「ヴィーナスの誕生」の主題は、「春(プリマヴェーラ)」の場合ですでに見てきたように、明らかにポリツィアーノの「ジュリアーノの騎馬試合(ジオストラ)」の詩(訳者注:Stanze、スタンツェ、が元の名称で、「部屋」の意味があるが、ここでは「韻律を活用して作られる韻文」で、それを作品の名称にしている)に由来している。その内容は、ホメロス讃歌の一つから派生した一節で、詩人はヴィーナスの誕生を描いている。キプロスの魔法にかかったような魅力的な島にあるヴィーナスの宮殿の門を飾る浮き彫りした彫刻の中に、彼は生まれたばかりのアフロディーテを見る。これは、神聖な顔をした乙女で、西風の神ゼフィロスのやさしい息に吹かれて、エーゲ海の波の白い泡の上で、花の岸辺に向かって静かに漂って来るという情景だ。

| |

Vera la schiuma e vero il mar diresti,

|

泡は真にあり、海も真にある、と汝は唱う、

| |

CHAPTER VIII

Heaven and earth, the poet sings, rejoice at the coming of this daughter of the Gods. The white-robed Hours wait to welcome her and spread a star-sown robe over her ivory limbs, and countless flowers spring up along the shore where her feet will tread. All of this exquisite imagery is faithfully reproduced in Sandro's painting. He represents his Venus Anadyomene laying one hand on her snowy breast, the other on her loose tresses of yellow hair - a form of virginal beauty and purity, as, with her feet resting on the golden-tipped shell, she glides softly over the rippling surface of the waves. He paints the shower of single roses fluttering about her form, and the winged Zephyrs clad in garments of pale mauve and green, and linked fast together as they hover in the air above, and waft the goddess to the shore of love. Following another of Alberti's suggestions, Botticelli introduces the actual "faces of Zephyr and Auster, appearing out of the clouds, in the opposite side of the picture, and blowing on the figures in such a manner that their draperies shall take beautiful folds in the breeze." After his wont, Sandro simplifies the composition, and in the place of the three Hours, mentioned in Homers' hymn, and in Poliziano's "Stanze", he shows us one fair damsel, the nymph of spring, wearing a white robe, embroidered with blue cornflowers, and girdled with convolvulus and roses, who springs forward with light and elastic step to offer Venus a pink mantle sown with daisies. In the laurel-groves that grow along the shore and spread out their boughs to shelter the new-born Aphrodite, we have, no doubt, a courtly allusion to Lorenzo's name. In the dedication of the "Stanze" Poliziano addresses his patron as the laurel under whose shade Florence can rest safely:

|

< <

第八章

天と地は、詩人が詠う、神のこの娘の到来で喜ぶ。白の衣をまとった時間の女神ホーラは彼女を歓迎し、その象牙のような身体に花を撒き散らした模様の衣をかけるために待つ。そして無数の花々が彼女の足が進む岸辺に沿って咲き出す。この絶妙な情景の全てをサンドロは忠実にその絵画作品で再現する。サンドロの描くヴィーナス・アナデュオメネは雪のように白い胸に一方の手を置き、他方の手はゆるく房になった黄色の髪の上に置く。乙女の美しさと清らかさを持った身体は、足を黄金色の開いた貝殻に乗せ、波のさざめく表面を滑るようにして来る。サンドロは、ヴィーナスの彼女の身体にひらひらと飛んで舞う一輪ごとのバラを降り注がせる。淡い藤色と緑の衣をまとった翼を持つゼフィロスは上空に浮かび、愛の岸に女神を吹き寄せる。アルベルティのもう一つの提案に従って、ボッティチェリは、絵の左側では、雲の外に現れる西風の神ゼフィロスと南風の神アウスターの実際の顔を描き込む。そして風の神々はそよ風を吹きかけ、その髪や衣服が風にたなびき、また美しいひだが出来るようにしている。サンドロはいつも通り、構成を単純にする。ホメロスの讃歌やポリツィアーノの「スタンツェ」に詠われている時の三女神の代わりに、一人の美しい乙女、春のニンフ、を示す。春のニンフは青いヤグルマギクの模様で刺繍され、ヒルガオやバラに帯のように取り巻かれた白い衣をまとい、軽くしなやかな足取りで跳ねるように進み、ヴィーナスに、ヒナギクを縫い込んだ上衣を差し出す。浜に沿って生え、生まれたばかりのアフロディテを守るように枝を伸ばしている月桂樹の木立に、疑いなく、ロレンツォの名前の上品な暗示を見ることが出来る。「スタンツェ」の献辞で、ポリツィアーノはロレンツォをその木陰の下でフィレンツェが心安く憩える月桂樹と讃えている。

| |

E tu, nato Laur, sotto il cui velo.

|

月桂樹が生まれ、その庇護のもと

| |

|

and he speaks of him elsewhere as the "laurel-tree who sheltered the song-birds who carolled in the Tuscan spring."

|

ポリツィアーノはトスカーナの春に祝歌を歌った歌鳥を庇護していた「月桂樹」としてロレンツォのことを別のところで話している。(訳者注:Lorenzoと言う名前にはLaurentisから着た人の意味があり、Laurentisはlaurelのある所である)

|

|

CHAPTER VIII

The sense of light and 、 movement is wonderfully given in wind-blown draperies and fluttering roses, in rippling waves and tossing locks that would have delighted the heart of Alberti, in the light and springing footstep and glad gesture of the nymph of Spring, in the gliding motion of Venus herself. Sandro never fashioned a fairer or more delicate form than this Goddess of love, whose ivory limbs may well have been modelled, as tradition says, from some antique marble among the statues of the Medici gardens. Some critics, indeed, have suggested that Botticelli borrowed the attitude of his goddess from the famous little statue known as the Medici Venus. Dr. Julius Meyer, with more probability, thinks that he found his model in another classical statue, which Benvenuto Rambaldi saw when he paid a visit to Florence, a hundred years before, and which, according to his description, agrees exactly in form and pose with the Venus of Sandro's picture. But the wan face of the goddess with her mournful air and sad, wistful eyes, is unlike any Greek or Roman image of the Heaven-born Queen of Cnidus and Paphos. All the sorrow of the modern world is there, the strange note of unsatisfied yearning which this painter of the Laurentian age has made peculiarly his own, and which appeals with a singular power to the children of the present day. This impression is heightened by the absence of sun, and the cold gray morning light that is slowly stealing over the distant bays and headlands of the landscape, and the long reaches of silent sea. We know not where Sandro caught this mediaeval note which blends so strangely with the bright myth of the old Greek world; but we feel there is no mere affectation in his melancholy, which finds expression both in his sacred and in his secular works, in his Madonnas and Angels as well as in his nymphs and muses. It may have been only the natural utterance of that sadness which seems to be the common heritage of the poetic temperament - the sense of tears in mortal things; or it may be the reflection of that sorrowful consciousness of the uncertainty of life, of human love and coming death, which threw its shadow over the gay festivals of those Renaissance days, and haunted Lorenzo's own songs with a mournful echo:

|

第八章

軽快でうきうきした動きの感覚は、風に吹かれた衣服の襞や羽ばたくように飛ぶバラに、海面の波紋やアルベルティの心を喜ばせた揺れる髪に、春の乙女の軽い弾む足音と喜びの中に、またヴィーナス自身の滑空するような動きに、素晴らしく与えられている。サンドロは、この愛の女神よりもより美しく繊細な形態を作り出したことはない。ヴィーナスの象牙色の肢体はメディチ家の庭にある古代の大理石の彫像から、伝統に沿って、形作られたのであろう。一部の批評家は、ボッティチェリがメディチ・ヴィーナスと呼ばれる有名な小さな彫像から自分の女神の姿勢を借用したと示唆している。ジュリアス・メイヤー博士は、100年前にベンヴェヌート・ランバルディがフィレンツェを訪れた際に見た別の古典的な彫像をサンドロはモデルにしたと考えており、彼の記述によれば、その形と姿勢はサンドロの絵のヴィーナスと全く同じである、とより確度の高いことを言っている。ランバルディのその古代彫像の描写を見ると、サンドロの絵のヴィーナスと形態や姿勢がぴったりと一致している。しかし、悲しみの空気を漂わせ、悲しげな思いに沈む眼をしている女神のはかなげな顔は、クニドス(プラクシテレスがアプロディテ像を製作した都市)やパフォス(訳者注:アプロディテ誕生の地)の天国生まれの女王のギリシャ的あるいはローマ的のどのような印象とも異なる。現代世界のすべての悲しみはそこにある。ロレンツォ時代のこの画家が自分自身のものとした満足することのない憧れの不思議な記録であり、今日の子供たちの心に並外れた力で訴えている。この印象は、太陽が描かれていないことと、遠くの湾岸や海岸の岬や穏やかな海の長い淵にゆっくりと忍び寄る冷たい灰色の朝の光によって強調される(訳者注:この「ヴィーナスの誕生」は修復が行われ、元々の光輝くような明るい色調に戻っている)。サンドロが古代ギリシャの世界の明るい神話とあまりにも奇妙に混じっているこの中世の調子をどこで知ったのかわからない。しかし、我々は、彼の憂うつの中に単に気取りと言うものは感じられない。彼の憂うつは神聖なものや世俗的な作品の両方で、すなわち聖母と天使だけでなく、彼の乙女や美神の両方でその表出がある。それは、詩人的気質の共通の遺産であると思われるその悲しみの自然な発話であっただけかもしれない。それは、死すべき者の涙の感覚、あるいは生命の不確実性の悲しみの意識の反映かもしれないが、人間の愛と来るべき死が、当時のルネッサンス時代の賑やかな祭りに影を投げかけ、哀れな響きでロレンツォ自身の歌につきまとった。

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

di doman non c'è certezza

|

明日は確かならず

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CHAPTER VIII

In this picture of the Birth of Venus the painter, we realize, has taken a new step in advance, and having freed himself altogether from the influence of other masters, henceforth relies entirely upon his own resources. The stiffness and rigidity of his early works have given way to perfect ease and grace, the old defects and difficulties have been overcome, and Botticelli has attained to a beauty of line and a decorative completeness such as has been rarely surpassed by any other artist.

|

第八章

「ヴィーナスの誕生」の作品では、画家は先に向けて新しい一歩を踏み出し、他の親方の影響から完全に解放されたので、その後は自分自身の能力に全面的に依存している。彼の初期の作品の堅さは、完璧な落ち着きと優雅さに近づいた。以前の欠陥や困難は克服された。ボッティチェリは線描の美しさと装飾的な完成度を達成しており、他の画家で彼にかなうものはほとんどいなかった。

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The other classical subject which Sandro painted about the same time, that is to say, soon after the canvas of Pallas subduing the Ccntatir and before his journey to Rome, in the beginning of 1481, is the painting entitled Venus (in the National Gallery).

|

サンドロが同じ時期に描いた他の古典的な主題としては、ローマへの旅の前で、カンヴァス画の「パラスとケンタウロス」の製作のすぐ後に、ロンドン・ナショナル・ギャラリー所蔵の「ヴィーナスとマルス」を1481年の初めに描いた。

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CHAPTER VIII